How do we define "England"? Flickr/Matt Buck. Some rights reserved.

Tonight I will talk about England. My home; my country. England is troubled, England is uncertain. And now, after the referendum, England isn’t even sure how we should be governed, where decisions should be made, or who should take them.

We don’t know where England is going; but England isn’t going away. And that’s a very strange thing. A dozen years ago a mini-industry declared England to be dead. Peter Hitchen’s ‘The abolition of Britain’ (which was really about England) was published in 1999, Roger Scruton’s ‘England an Elegy’ in 2000, and Geoffrey Wheatcroft’s ‘The strange death of Tory England’ in 2005 all said England was dead. They didn’t mean, of course, that England had disappeared, but a particular idea of England had died. One embodied perhaps in this man:

This man is Percy Spence, my maternal grandfather, in the uniform of the volunteer East Surrey Yeomanry in 1908. You won’t need much persuading that Percy was conservative large c and small. He was upright in character as well as bearing. He believed in order and deference, responsibility and service. But we have two grandfathers, of course:

This is not such an evocative photograph but you may not need too much persuading that Albert Denham drove the steam express from Kings Cross to Edinburgh. He was a gifted musician and self-educated union man, a member of the Independent Labour Party. He was a friend of the radical Yorkshire miners’ leader Tom Williams, throughout what my father always called the Great Strike, not the General Strike.

In popular political writing – like Simon Heffer on the right or Bill Bragg on the left – we are often asked to see the true history of England as either conservative or radical, but I have a problem with that. Asking me whether England’s real story is radical or conservative is liking asking me which of my grandfathers is most English. Culturally, personally and politically, I’m the product of the daughter of the Surrey conservative and the son of the Yorkshire radical; the sort of marriage that might never had happened if it had not been for the Second World War when both were in the RAF. That war, like other wars, conflicts and disasters, changed England.

Events change us as a nation - these events change how we think about ourselves - they give us new stories about ourselves – Waterloo, Empire, Blitz. But when we change, we then insist that England has always been like this. Despite what I just said about my grandfathers, though we are the product of all our history, we choose which history we want to tell.

England doesn’t have a founding myth of who we are. The French cut off their king’s head and, overnight, became citizens. When we did the same we decided, on balance, we would rather remain subjects. We had no defining moment of national unification. Even if Scotland had voted Yes, England would still begin and end where it has for hundreds of years.

We’ve never been invaded, so when we were occupied by the Dutch we called it a glorious revolution. We broke with Rome after hundreds of years and said the Church of England embodied an unbroken tradition of English Christianity.

We don’t mind that the Magna Carta was not, as its authors claimed, a restatement of ancient liberties. It is what Magna Carta came to mean, in law and in the popular imagination that matters. Nothing could be more English than David Cameron telling us how important it is while admitting he didn’t know what Magna Carta meant.

That’s the English gift. We don’t discover our England in the history books; we create England, again and again, from the parts of our history which make most sense to us today. Events happen, things change, we change, our view of the world changes, the stories we tell about ourselves change. And then we declare, ‘this is what England always was and always will be’.

At the very time those obituaries to a particular conservative England were being published, we seem to have started to feel more English:

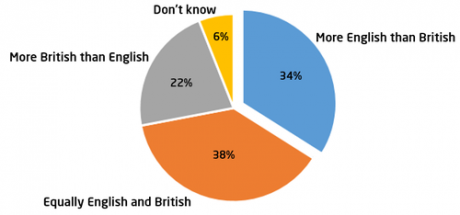

Source: British Future 2013

We can ask people whether they are English only, English and British or just British. Over the past ten years or so, the English only group has expanded, the British only group has shrunk. More say they are more English than British: over 70% have English either as their prefered or shared identity.

These figures – and some polls show those with an England preference at nearly 50% - have risen sharply. We are not about to become only English but our sense of Being English matters more and more; our rising sense of Englishness matters to us. The days when England didn’t need to be English because it was good enough to be British are gone.

What will England be?

England is my home. England is our history. But England is changing. What will our English story be? We don’t know what these newly English imagine England to be. The researchers who ask about national identities don’t ask enough questions about what it means.

We do know the new English are more likely to be worried about immigration and to be anti-the EU. They are more likely to vote to the right. It is true that a majority of Labour voters also prefer an English identity, but this doesn’t feel like a radical socialist England replacing the older conservatism.

On the other hand, take time talk to those who say they are English and they’ll often tell you they feel powerless, that they are losing out, that no one listens to them. Unfairness, exclusion, powerlessness; these have always been the drivers of radical England. And, of course, part of England’s radical tradition always responded to change by trying to stop change happening. The agricultural rioters who gathered under the banner of Captain Swing riots in Hampshire and Dorset, the machine smashing Luddites in northern England, in some of the restrictive practices and craft demarcation of the older trades’ union movement. All people threatened by change who Just wanted to make it stop.

The pollster Peter Kellner tell us that UKIP voters are united in one belief; that everything was better 50 years ago. But that doesn’t mean that Australian academic Ben Wellings was right to equate UKIP’s rise with English nationalism. UKIP draws on some of these sentiments but the sheer numbers emphasising their English identity is far greater than have ever expressed support for that party. In any case, it’s only politicians and political scientists who leap straight from identity to party allegiance.

People, like me, who have spent too much time in politics, have all too easily missed what is happening outside. As Mike Kenny has recently documented, the modern exploration of Englishness actually began well outside politics with plays like Jerusalem, Elmina’s Kitchen, and Playing with Fire. Novels like White Teeth and England, England. The poet laureate Andrew Motion and other poets creating a new liturgy for St George, Damon Albarn’s opera Doctor Dee. Films like This is England.

The revival of the English folk tradition reflects the swirl of ideas around. It can hark back to an idealised, rural idyllic past. But it can also the basis for new music that mixes the traditional with new influences and cultures. The St George’s Cross no longer belongs to the extreme right. There are more and more St George Day celebrations, as diverse as Englishness itself. That’s a lot of people wondering about being English. There’s nothing here to suggest that exploring Englishness must, inevitably, be reactionary, zenophobic or inward looking.

I don’t think it is hard to understand why we are asking these questions now. A globalising world is not leading to a globalised citizenship. Everywhere people are responding by looking to the local for a sense of identity and we are no different. Over time, confidence in the core concepts of Britishness: of Empire, a dominant global economy, the provider of a comprehensive welfare state, has faded. As the notion of Britain has beome less distinct, so we become more interested in what it means to be English.

Wales and Scotland have asserted themselves. If we can’t lazily assume that English and British are pretty much the same any longer, then who on earth are we? We are troubled by the European Union, torn between the common sense of cooperation and stories of standing alone.With the closing of Portsmouth’s warship yard – as work transfers to Scotland – goes the last of the great manufacturing and engineering work places that once dominated our local economy; and with them went the status, security and social institutions they provided. Our villages and countryside have changed. Our communities have changed, not least with immigration, the most dramatic demographic change in our history. Parts of England look, feel and sound different.

Re-imagining England

England has changed, so England must be made again..

But, in truth, England seems fearful today. Never in hundreds of years have we seemed as fearful of the world, fearful of Europe, fearful of our engagement with other countries, fearful of foreigners. Can we imagine – re-imagine – an England without that fear? Is there an English story, true to our history and traditions that can meet the needs of the 21st century? Is there an England that can give a voice to the voiceless? Can we find an England that has the confidence to face the world?

Let me reinforce why this should matter, even to those who are not much taken with national identity. I am a patriot by birth but by career a progressive politician. What I have learned is the importance of the stories we tell about ourselves. A common story has shared values, and the values we share shape the society we can build.

Why is the National Health Service so popular, even at times when it doesn’t perform well? Because it has a fundamental value ‘we all pay in and it’s there when we need it’. That’s not a funding policy; it speaks to a deep notion of the sort of people we want to be as a nation.

Why is our current welfare system so unpopular? It’s because our deeply held values are of contribution and reciprocity, not just rights. We think you should pay in, not just take out. A system that seems to reward need alone and not contribution is out of kilter with our common values.

Our national story, our shared values, determine what type of practical policies will get public support. So what we imagine England to be will determine what sort of society England can become. What ideas might be lurking in our collective memory and traditions, which can underpin the future as surely as our shared values underpin the NHS? I will not be offended if you tell me this is bad history. The one thing that is clear about English history is that it is not the best history that matters but the history that is best believed.

What I am sketching out is not a study but a project. Our challenge is not to wait and see what happens, but to help shape England. One of the reasons I took up the offer of joining Winchester was the hope that here, in England’s ancient capital, we could develop a centre, a place of debate, discussion and research that might play some part of shaping England’s future.

Understanding the radical tradition

The radical tradition is not the history of England, but it is part of it.

Ordinary people struggled together for justice; for the bare necessities to live, for basic civil and political rights, for a better life. We all know the high points: the peasants’ revolt, the levellers and the diggers, non-conformist dissent, the campaigns against slavery, the chartists, the trades union movement, the suffrage movement, and into modern times the peace movement, the women’s movement, gay rights and environmentalism. Win or lose they changed our country because they changed our view of what is possible.

After 40 years in politics I can tell you a secret: the great challenges are almost never first defined inside a political party; and the great answers aren’t first found in political parties either. They come from the movements outside. Sometimes they enter the mainstream of politics slowly; sometimes quickly. It took a hundred years for the demand for a minimum wage to become law but just ten years for the Living Wage to be at the centre of public debate.

The radical tradition is of collective action; of giving a voice to the voiceless, but the great statements of English radicalism never say that the nation, the people, the folk or the class is more important than the individual. Instead change was needed in order to enjoy the rights of the freeborn Englishman. Gendered language aside, these radicals both advanced common interests and treasured long held views of individual rights, of individual conscience and dissent.

English radicalism is special in another way. The movements did not just demand change, they created change. They created new institutions – workers’ libraries, cooperatives, friendly societies. They celebrated culture in choirs, bands, and banners. They organised for fun and recreation into a myriad of sports and social activities. English radicalism challenged power and injustice, but it often had much in common with a much broader English tradition: the creation of institutions, essentially private in nature, but which fulfil a clear public and social function.

Our universities are amongst them – very different to the state directed institutions of continental tradition. The trade union movement itself. Occupational pension schemes. Friendly societies. The National Trust. Charities and voluntary organisations. These make up a tradition of independent, collective, self-organisation. While they sometimes need a legal framework and funding, their effectiveness depends on their freedom and autonomy.

The richness of this civic life and enterprise is distinctively English. Few other countries enjoy the richness of our voluntary movements or the autonomy of our key institutions. But we have been careless with it. We killed occupational pension schemes. We’ve made charities sub-contractors to private monopolies. We need to protect and revive that radical tradition.

The common good

We are not, by temperament, an anarchistic nation. We want government, but we want it to be good, fair and competent; and we have a strong notion of the common good.

When Wat Tyler addressed the young King Richard II in 1381 he didn’t threaten to overthrow the monarchy. He set out the responsibilities of rulers. Rulers should not use the law arbitrarily:

‘There shall be no law but the law of Winchester’

Other powerful people must use power responsibly:

‘No lord should have lordship save civilly’

Institutions that had accumulated wealth unjustly should have it redistributed:

‘Clergy already in possession should have a sufficient sustenance from the endowments and the rest of the goods should be divided among the people of the parish’

And in rights and in dignity we are all equal:

‘No serfdom or villeinage, but that all men should be free and of one condition’

Time and time again the English have said the same. We will have government, but the legitimacy of government derives from its ability to deliver for the common good. There will be powerful people, but our measure of them is whether they meet their responsibilities to wider society.

However, our society today is wildly unequal in wealth but also in power. Everyone knows in their bones that the rules are different for those at the top. For decades we have been told that the accumulation of great wealth is the right and just outcome of a market economy. We have been told that this is a natural law in which morality has no role to play. On the other hand, the historic notion of the common good challenges that self-serving ideology. The common good demands that we judge a society, its government, its powerful, by whether they deliver their obligations to the many. If, once again, we could make the common good the measure of England it would change what we think we can do.

The common good can give us a new sense of national economic purpose. The loss of major companies, the dominance of the global banks in London, the relative neglect of innovation and manufacturing, the skill shortages and under-utilisation of talent in poorly paid and unproductive jobs – these are all symptoms of an economy run in the interests of a few. The common good can give us the rules for reshaping the economy. The common good can provide the values that can be shared in the boardroom, call centre, hospital and shopfloor. The common good tells us what behaviours we value and those that we don’t.

Migration

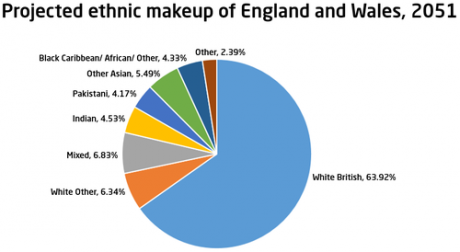

England is always changing, but few changes have been as rapid, and as visible as the immigration of recent years. In 30 years or so, around a third of our population will have ethnic minority backgrounds:

Source: Runnymede Trust 2010

Around 30% will not be white. Many parts of England will look, perhaps sound, very different. Minority communities today are much less likely to say English than British. Younger generations are changing but the disparity is marked. We can all have multiple identities. But a nation cannot work if we can’t agree what nation we are, and if that disagreement is on ethnic or racial lines.

English has to be an identity we can all share, or England itself will fail. Even though the history of our island has been absorbing the impact of newcomers, nothing quite like this has happened before. Still, there is enough in our past to guide us today. The English have never been defined by our genes, but by our institutions, our customs, the way we do things.

There is, of course, a limit to how fast any nation can be expected to change. And our deeply held values cannot be negotiated:

- - Everyone should play by the same rules,

- - You have to pay in, not just take out,

- - The radical demand for freedom from exploitation in the workplace,

- - The popular tolerance of live and let live.

Migrants have come from many places but most have some historic link. When I told a young Southampton councillor that my uncle was on Southampton’s war memorial having been torpedoed on the way to the Far East, she told me her Sikh grandfather had been in the same army in the same conflict. In sharing two stories the south Asian presence becomes not an accident of history, but a shared history of sacrifice and service. When we share our stories we can understand how we all came to be here.

No one will come to a party to which they’ve not been invited; I believe that being English belongs to everyone making their home and life here. Racists will deny this. But, let’s be honest, well meaning liberals who say ‘we can’t really talk about England because of minorities’ are in their own way, suggesting that Englishness is not for all. We need to understand that place matters.Everyone said how calmly the English responded to the 7/7 bombings. Yet 40% of those Londoners weren’t born here. Our local identities communicate values and belonging.

Above all, it’s time to recognise that, while multi-culturalism rightly taught us to respect our differences, it did too little to develop the values and ideas that must bind us together. The challenge for today is nothing less than nation-building – building a nation anew. Consciously developing those common stories, common values, that explain who we are, how we came to be here, and where we are going.

In 50 years time our grandchildren may well look back and say this was the moment that England rediscovered the confidence to face the world, to be a global player.

We will explain much of our power and influence in the world by the extraordinary advantages of the English people. Drawn together by England’s greatest gift the world, the English language, we became, almost unique in the world, a nation that not only speaks the global language but has family, culture and historical links to every part of the globe. We will remember the thousands of black people in Elizabethan London, the contribution of the Huguenots to our woollen industry, the enterprise of the Jewish refugees, the contribution of generations of new migrants to our science, innovation and enterprise. And then we will say, not that England was always like this; but that England has always been built by all the people who lived here.

A sense of place

In every telling of English history, place has mattered. Our island status has governed our relationship with the rest of the world. Our weather has shaped our relationship with our environment. Countryside has retained an iconic importance long after most people ceased to living or work there. Access to land – for livelihood and leisure - shaped our radical traditions. And, with all due respect to Basingstoke, we prefer to live in places that have grown organically not been dropped down by planners.

And where we live is part of our identity. We are Geordies, Westcountry, Cornish, Brummies, Londoners; our sense of place is deep. Perhaps surprisingly, its about to come back into its own. England is highly centralised, and has become more so in my political lifetime: when I was a Hampshire county councillor 64% of local finance was raised locally, now it is 40%.

The development of the modern state replaced not just the historic units of local government but the places and institutions that drove our great cities and industrial development. Before the Second World War, Douglas Jay said ‘the man in Whitehall genuinely does know best’. Nye Bevan wanted the sound of a falling bed pan in the new NHS to be heard in Whitehall. Yet today the civil servant Whitehall doesn’t even know what is going on. A cacophony of falling bed pans and other data overwhelms their ability to make sense of it, let alone manage it.

The thrust of technocratic reports from Michael Heseltine and Andrew Adonis is that England’s governance must be decentralised. This is grasping the future, not a retreat into an idealised past when giants like Joseph Chamberlain in Birmingham (and our own Sir Sidney Kimber in Southampton) shaped our cities. We can do stuff now we couldn’t do 30 years ago. The connectivity of the web means that today we can be both more local, and more aware of what is happening globally than ever before. Open Data means everyone will know how well their services are performing. But this will only fly if it’s linked to our historic sense of place.

Whitehall’s instinct will be for neatness. To impose constitutional change like the Roman’s built towns that disappeared as soon as the legions left were gone. England’s internal constitution must evolve more like an Anglo-Saxon market town; it should be messy, proud not to be the same everywhere. That’s more in keeping with our history and our English eccentricity.

England must get what England wants

So what about England itself? David Cameron has called for English Votes for English Laws. Ed Miliband called for a constitutional convention and proposed replacing the Lords with the Senate of the nations of the UK.

Change is coming and I start from a simple proposition: England must get what England wants. We must take our decisions in a manner which England determines, just as the Scots and Welsh have been able to do.

It is self-evident that as more powers are devolved to Scotland and Wales and indeed Northern Ireland, the less acceptable it can be for MPs not elected by English voters to determine what happens in English schools, hospitals and universities. Change is perhaps more complicated than has been suggested, if we want both stable government and to keep the Union together. But this isn’t a debate than can be silenced. And nor can it be determined in a Whitehall committee.

If England is going to get what England wants, this debate must be taken up by the people of England. In our communities, in local councils, in faith groups, business associations and voluntary organisations. We have the chance to demand decisions be taken closer to where we live, and we have the chance to decide how we want England to be governed. That’s too important to be left to the politicians in Westminster and it needs to start now.

I am a Unionist and I was pleased there was a No vote. But if I am honest, you have to be quite an optimist to believe the Union will survive as it is now evolving. The once great Conservative and Unionist Party is now to all intents and purposes the English National Conservative Party, while Labour has, as yet, no distinctive English voice of its own. Also, in my view, only when England is confident in itself will we be able to determine our relationship with Europe.

Re-imagining England

For large periods of time, being English seemed to look after itself; we didn’t talk about who we were because we knew who we were. But at other times of great upheaval; it has mattered greatly, and this is one of those moments.

For all the reasons I have touched on tonight; economic change; the powerful failing their obligations; government systems that cannot work; our fears of the world outside and the strangers within; this is a time for nation building. England is making itself anew. For those who love our country, this is no time to stand and watch, but time to be part of that process.

I have only covered part of the canvass here. The church has been crucial in defining England in the past; faith – many faiths – must help define us now. This is above all for the rising generation.

At Winchester the University is working with college students in Southampton to ask what sort of England they want to create. That work has grown out of our St George’s Festival, and next year we will bring together many of those who organise popular festivals of England around St George and Shakespeare’s birthday as we begin this work of exploring our new and old nation.

National identities are created, not discovered. We draw on our histories, but we can choose the parts that are of most value to us today. In this text I have re-imagined my country:

An England of the common good. Where the quality of government, the status of the rich, the morality of the powerful is judged not by what they take for themselves but how they deliver for the common good.

A well governed England where public policy sits easily with the values of the English people.

A radical England, where we are prepared to struggle together to fight injustice but also to defend individual liberty; where we create new institutions together, making demands on the state but not dependent on it or subject to it.

An England at ease with its diversity, forged together in one nation and confident to face the world.

An England where decisions are taken as close to the people as they can be, where we value our local traditions and identities.

An England governed in the way the English decide we want to be governed, supporting the Union but not carrying it.

That’s what I have imagined, so think what we could imagine together.

This post was cross-posted with permission from John Denham's blog.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.