JIM GERAGHTY: Ultimately, Math Ended The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

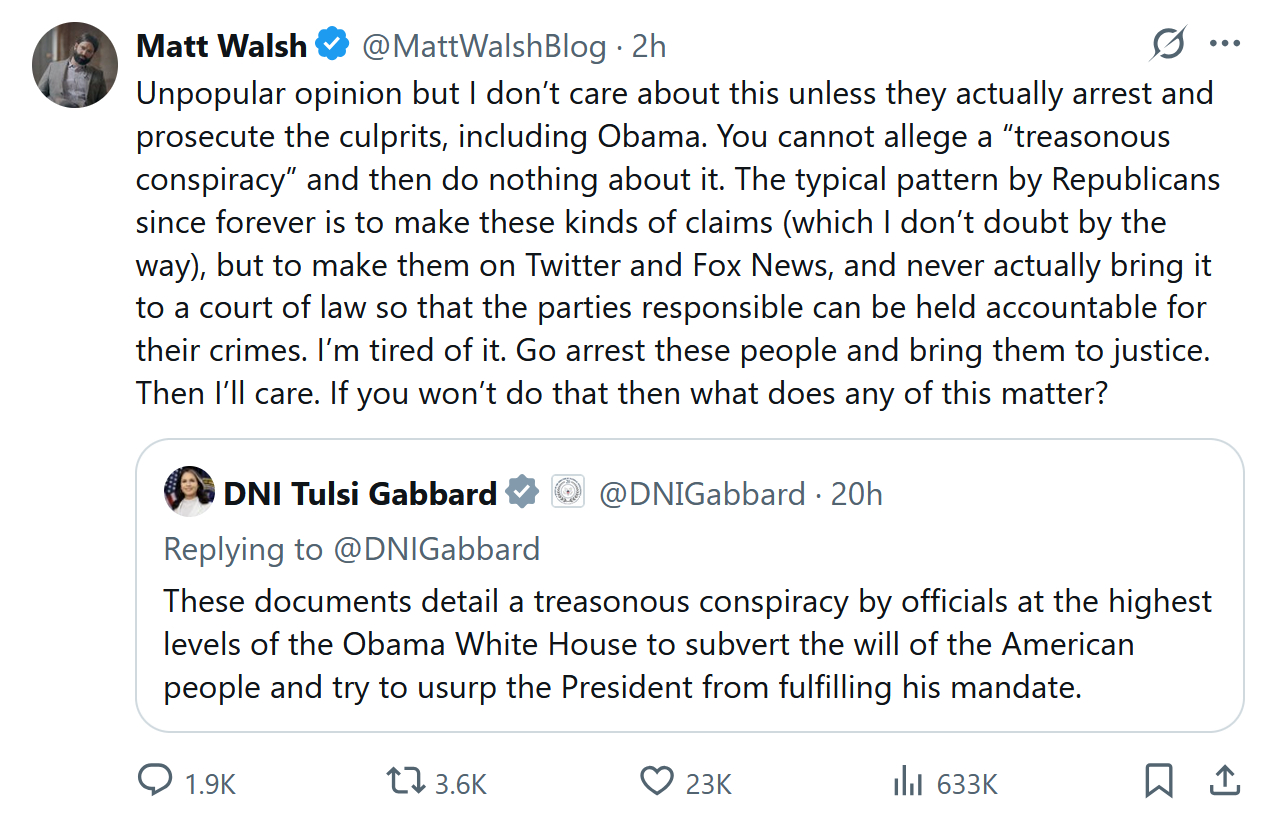

You can be like Chris Hayes, Brian Stelter, Vox, The New Republic, Adam Schiff, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and other progressives, and choose to believe you live in a world where the ending of The Late Show is a sinister plot by spineless, cowardly corporate executives who are terrified of irking President Trump and who desperately want the Federal Communications Commission to approve the merger of CBS’ parent company, Paramount Global, with Skydance Media. (And, it should be noted, Colbert’s choice to turn the show into a four-nights-a-week version of the speaker list at the quadrennial Democratic National Convention.) That is a dramatic world, with noble heroes and dastardly villains, plotting against the interests of the public, punishing a brave comedian, smashing dissent, and bending the knee in obedience to a ruthless, vindictive, power-mad president.

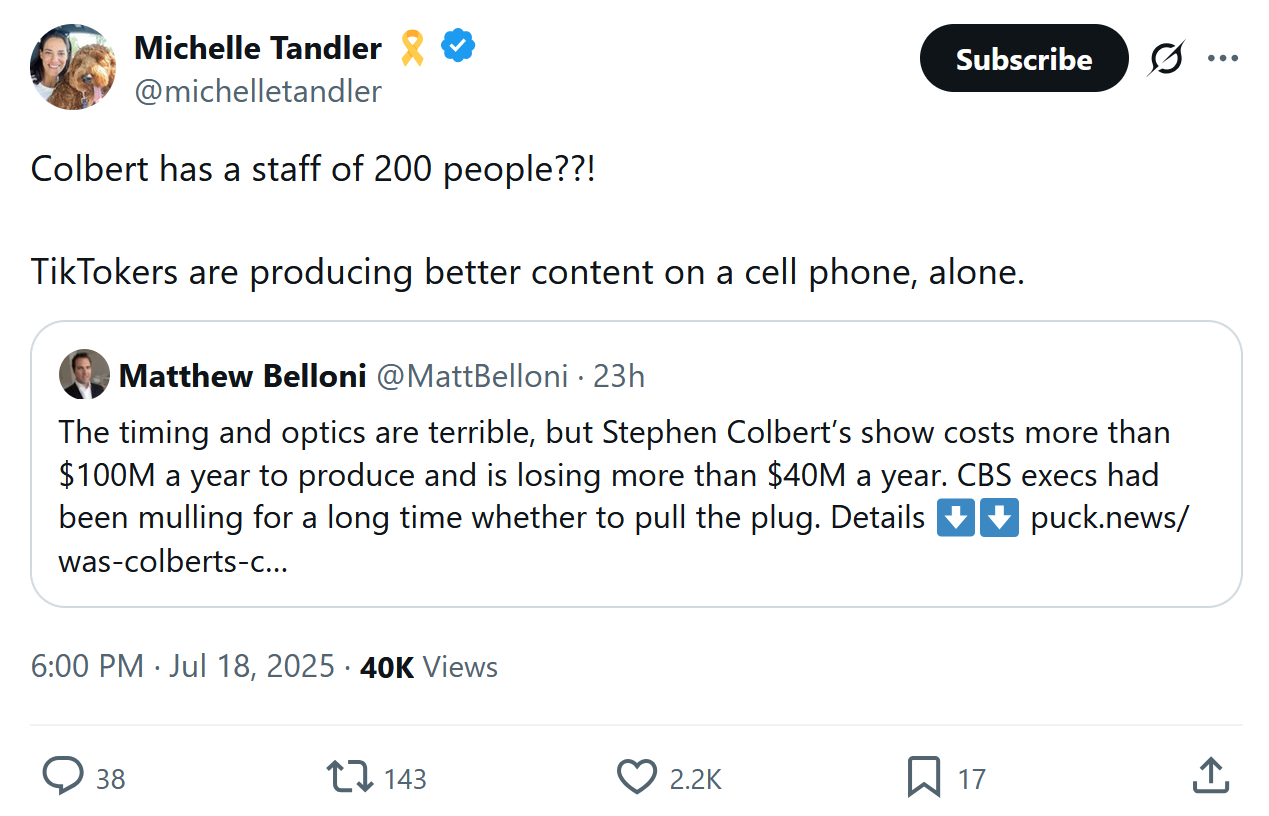

Or you choose to believe you live in a world where the ending of the show is a reflection of the fact that CBS was losing $40 million each year on the show, as the Wall Street Journal reports today. And as much fun as it would be to blame Colbert for being greedy and making the show unprofitable with his $20 million per year salary, with numbers like that, the show would still be unprofitable even if he worked for free.

Reuters adds, “the show’s ad revenue plummeted to $70.2 million last year from $121.1 million in 2018, according to ad tracking firm Guideline.” If a show’s ad revenue gets nearly cut in half over a six-year period, that is a serious and worsening problem, and an indication that it isn’t a reflection of a one-year blip or temporary economic pressures.

That is a much less exciting world. In that world, Colbert’s nightly denunciation of Trump was not much of a factor in the show’s fate, other than maybe alienating roughly half the potential audience for the show.

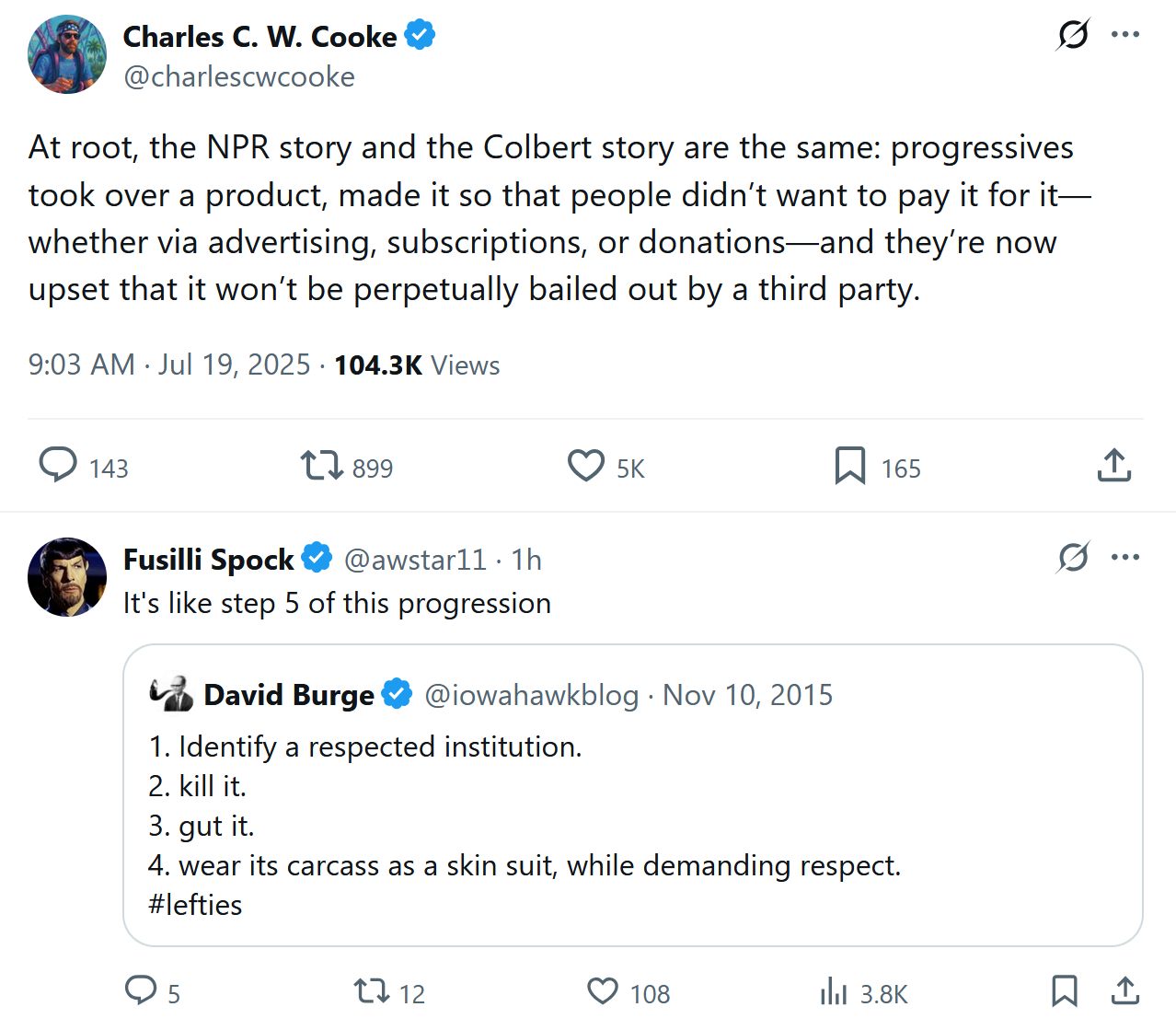

Charles Cooke adds:

I don’t think they envisioned that there could ever be a step five. As Abe Greenwald of Commentary wrote in his newsletter yesterday:

Liberals are learning that there’s no such thing as lifetime tenure, eternal cultural dominance, and unending access audiences or the levers of power. To be honest, many of us outside the liberal establishment are learning it too. I’d become half-resigned to the endurance of the liberal Pangea. But the ground is now shaking beneath everyone’s feet.

Related: From the Washington Free Beacon on Thursday: NPR CEO Katherine Maher, Who Once Said ‘America Is Addicted to White Supremacy,’ Now Says NPR Needs Federal Funding To Support ‘Rural Communities.’

NPR CEO Katherine Maher, who once called America “addicted to white supremacy,” is warning that looming federal funding cuts to her left-wing broadcast organization will disproportionately hurt rural communities.

“The primary impact of this potential rescission is going to hurt communities where they need support most, which are rural stations—stations that serve communities that do not have access to other forms of local news, emergency reporting, emergency alerting,” Maher told CBS News on Thursday morning, just hours after the Senate voted to cut funding to public broadcasting.

“I think that the place where we’re seeing the most traction is senators who represent communities where there are large rural communities, large tribal communities,” she said Wednesday on CNN. “Broadband service is not universal, and heck, cell phone service is not universal.”

Those comments follow Maher repeatedly disparaging white Americans.

A decade ago, Rob Long wrote that Johnny Carson broadcasted in a television universe that consisted of “three big channels—and maybe an old movie on one of those fuzzy UHF stations—so if you didn’t like what was on, you were out of luck. Network television didn’t compete with cable channels or Hulu or Amazon Prime. It competed with silence.”

Robert Conquest’s First Law of Politics states that “Everyone is conservative about what he knows best.” But I really don’t think he was envisioning the mindset of network TV and public radio executives who convinced themselves — or at the least tried to convince others — that they still worked in the mass media world of 1972.