Verwoerd: Why He Still Matters

Andrew Peters, American Renaissance, February 17, 2017

On September 6, 1966, white South Africans were plunged into shock and mourning by an act of political violence that was then largely unprecedented in their country, although terrorist attacks would grow commonplace in the following decades. That day witnessed the assassination of South African Prime Minister Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, the so-called “Architect of Apartheid.” Verwoerd was stabbed in the heart by a mixed-race illegal alien with a communist background, who had infiltrated the Volksraad (House of Assembly) in Cape Town as a parliamentary messenger. A.E. Trollip, a member of Verwoerd’s cabinet, summed up the collective grief: “I don’t think I need to say to my colleagues here in the Senate that Dr. Verwoerd was South Africa, and when the dagger was thrust into his heart, it was thrust into the heart of South Africa.”

Why did Verwoerd mean so much to the whites of South Africa in 1966? To answer that question is to explain why — even after half a century — his ideas, values, and legacy are still deeply relevant for whites everywhere.

The Policy of Separate Development: Minister of Native Affairs, 1950–1958

Following a distinguished academic career at the University of Stellenbosch, Verwoerd’s political activism began as editor-in-chief of Die Transvaler in 1937. This newspaper was founded to advance the cause of Afrikaner nationalism, in opposition to British imperialism and racial liberalism.

After the National Party returned to power in the general election of 1948, Verwoerd was (in 1950) appointed Minister of Native Affairs, with responsibility for the Bantu, the numerically overwhelming “blacks” of South Africa (as opposed to the much smaller mixed-race “coloured” population). Verwoerd occupied this portfolio until his elevation to the premiership in 1958, which he held until his death. He thus played a key role in formulating and defending South Africa’s racial policies during the critical early years of Apartheid.

Let us be clear about the Afrikaans word “Apartheid.” From the beginning, it was seized upon by international media and invested with a sinister coloring that English equivalents such as “apartness” or “separateness” do not have. Nowadays, it has become the ultimate slur that progressives use for any population policy they don’t like.

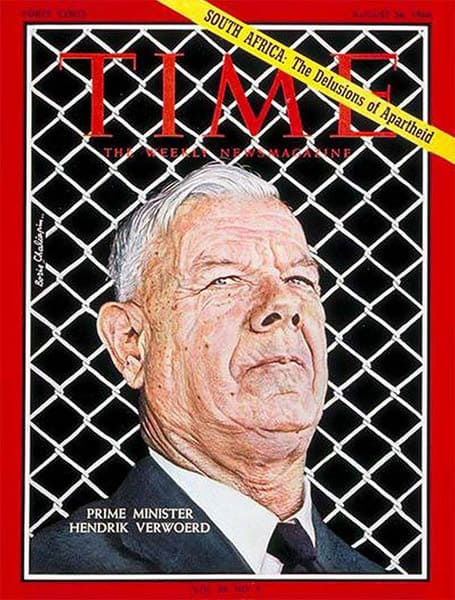

How liberals saw Verwoerd.

Verwoerd himself, an eminently practical man, was never preoccupied with terminology; the goal was what mattered. In one English-language interview, he suggested that “good neighborliness” might have been a more helpful phrase to characterize his government’s racial program, since neighbors can help one another in the Christian spirit but lead distinct lives in separate spaces. Verwoerd’s own preferred terms in Afrikaans were aparte ontwikkeling (“separate development”) and eiesoortige ontwikkeling (“development in accordance with one’s own special character”). “Separateness/distinctness” and “development” were equally central to Verwoerd’s racial objectives.

Verwoerd advocated separation because he predicted a nightmare for his people under any other policy. In South Africa, as Verwoerd argued with inexorable logic, racial integration would eventually mean domination by the numerically superior Bantu. Either the whites could be masters in their own land, or else they would be overwhelmed in the Bantus’ land. There was no happy middle path between these two alternatives, however much the liberal opposition liked to pretend otherwise.

Verwoerd thus insisted: “The path of integration can be slowed or accelerated, but it inevitably leads to Bantu supremacy. There is no escape from that. The result must be an injustice against all minority groups.” White acceptance of racial integration was tantamount to collective suicide: “It is a fundamental right of the white man, too, to be able to protect his own nation from ruin. Every nation has the right of survival. It is the most basic human right. It is a fundamental right to maintain your nation and to protect your identity as a folk. This is what lies at the foundation of our whole policy.”

To safeguard the future of whites, Verwoerd pushed through a set of laws designed to achieve the maximum separation between white and Bantu in terms of living space, social intercourse, sports, education, political participation, economic activity, and so on.

Under the previous United Party government, blacks had been allowed to stream into white cities. White capitalists encouraged this, since it meant an ever-expanding pool of cheap labor, and their wealth kept them insulated from danger and social disruption. But the influx of blacks was a financial burden on white taxpayers, who had to pay for housing and other services for the newcomers, and it brought crime and overcrowding for blacks already there.

Verwoerd sought to reverse this trend by two methods, “separateness” and “development.” First, he imposed tighter restrictions on the movement of Bantu to the cities, and took steps to ensure that the Bantu already present were housed in clean, safe neighborhoods as far as possible from white homes and workplaces. Needless to say, these steps were greeted with howls of outrage by both the labor-hungry capitalists and the liberal media, churches, and opposition parties.

But the second set of measures, despite being just as critical to Verwoerd’s long-term project, has been largely ignored by his detractors. In order to stop black immigration into white areas, Verwoerd saw that it was imperative to provide blacks with opportunities in their traditional homelands. The development of Bantu areas into self-governing, economically self-sufficient communities was an indispensable safeguard for the white homeland, too.

In order to help black development, Verwoerd applied the lessons from the Afrikaners’ own liberation struggle against the British. The two Afrikaner republics in the Transvaal had been invaded by foreign capital and workers during the gold-mining frenzy of the 1880s and ’90s. During Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902, Britain conquered the republics and thereafter ruled them, at first through British colonial administrators and then by proxy through imperial puppets. The Afrikaners were also the target of a campaign of cultural Anglicization, especially through the education system, by which Afrikaner youth were to be stripped of their language and traditions. Through his columns in Die Transvaler, Verwoerd had fought for political and cultural freedom for his nation, and as Minister of Native Affairs and then Prime Minister, he extended this concern for national independence to the Bantu peoples as well.

In Verwoerd’s plan, the Bantu were to enjoy increasing political autonomy as their capacity to exercise it increased. The Afrikaners had resented Britain’s attempts to force them into the British mode of monarchical government, alien to their own republican heritage; in the same spirit, political development for the Bantu was to be rooted in a traditional tribal structure that was adapted for modern needs. Verwoerd declared, “Genuine development of their own for the Bantu must be built up on the basis of enduring values in their national character, and these can never be replaced by forms of civilization that are pasted onto the Bantu community from the outside.”

On the economic front, white capital was not to be permitted to take over the Bantu homelands in the way that the Transvaal had succumbed to foreign capitalists in the 19th century. Instead, the natural and human resources of the Bantu were to be developed by and for themselves, on the basis of the Bantus’ own ability. This would take time. In the meanwhile, to attract Bantu back from white cities to their homelands, white-owned industries were to be established near the borders of those homelands, so that Bantu could live in their homelands while still working profitably for whites. Exploitative white ownership within the homelands would be forbidden.

Verwoerd’s policy for Bantu education contrasts sharply with the current tendency in South Africa to purge Afrikaans language and culture. Before Verwoerd, the education of the Bantu — frequently in the hands of British missionaries — was meant to turn Bantu children into “black Britons,” estranged from their families and communities. Verwoerd sought to change this, in part by fostering education of Bantu children in their own languages; mother-tongue education had also been a key component of the Afrikaners’ struggle for national survival against Anglicization. In addition, Verwoerd tried to involve Bantu parents more closely in their children’s education, which had likewise been a recurrent demand of Afrikaner parents under British rule.

In a speech of 1955, Verwoerd summed up the difference between the two approaches to education, national vs. assimilationist: “[In the past, the Bantu] thought that there are only two alternatives, either to shake off everything that is Bantu and to assimilate as much Western civilization as possible, clothed in English, or to remain Bantu and uncivilized. That you can remain Bantu, that your Bantu language can become a medium of civilization, and that you and your whole community along with you can in this way reach much sooner a higher intellectual, social, and economic standard of life, is for them a brand-new and almost unbelievable idea.”

Verwoerd’s support for distinctively Bantu education was not mere rhetoric. Between 1955 and Verwoerd’s death in 1966, the number of Bantu children attending school more than doubled, from 1,000,000 to 2,150,000. According to UNESCO, Bantu literacy rose from 37 percent in 1956 to 57 percent in 1968; sub-Saharan Africa as a whole did not attain this level until the late 1990s.

Support for African traditions and culture is therefore central to Verwoerd’s legacy, but today, anything that was Afrikaans — institutions, schools, street names, farms — is being taken over and suppressed by blacks. Verwoerd had a sobering warning about the politics of racial envy. In a speech to Bantu leaders inaugurating the first step toward self-government in the Transkei homeland, he said:

I must warn you that there are people who become envious when they look into another man’s garden. If they see a large tree full of fruit there, then they say: ‘We want to have it.’ The man who attempts or desires to steal from another man’s garden, however, always forgets to take care of his own. While he leans over the fence and looks and looks, he forgets to water his own tree. He forgets to spray against insects, and when he turns around, he discovers that the branches are withered and the fruit isn’t there or is inedible. . . Therefore you must not look with envious eyes to the more developed tree of the whites, because then you will neglect your own little tree that one day will be a great tree too. It has often happened that, when one person covets another’s property, they come to blows. Meanwhile, the thing that they both want to possess falls apart or turns rotten! Or the axe can be used to cut down the tree, and then no one has any fruit! We mustn’t be like that in South Africa. Let’s take the trees of separate development, and each care for his own tree.

In Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, in the “rainbow nation” of the new South Africa, and even in American cities, blacks seem more eager to cut down the trees belonging to whites than to cultivate their own.

Crowning Achievements: Prime Minister, 1958-1966

Verwoerd’s eight years as Prime Minister marked the culmination both of the battle waged against globalist imperialism during his time as editor of Die Transvaler and of his project, as Minister of Native Affairs, to develop separate homelands for whites and Bantu.

The policy of separate development reached its climax with the grant of full self-government to the Transkei in 1963. Although anti-Apartheid activists heap scorn on the creation of autonomous Bantu homelands as yet another instrument of racist oppression, there is no doubt that Verwoerd sincerely intended them as a way to encourage the Bantu to live out their national aspirations without endangering white survival. Verwoerd’s ultimate vision for South Africa was comparable to the original conception of the European Union as a free economic association of sovereign states, each with distinct national identities.

However, Verwoerd’s resolve as Prime Minister to continue along the path of separate development forced South Africa into increasing isolation. As the United Nations began to admit new non-white members — many non-democratic or communist — UN pressure on South Africa intensified. But Verwoerd is especially remembered today for his defiance of the British Commonwealth, which, like the UN, became more hostile to South Africa with the addition of members from newly independent non-white nations. Of course, most of these governments were in no moral position to criticize South Africa about democracy or social justice, but this diverted domestic opinion from their own mismanagement and corruption — and Britain was happy to go along.

The conflict between Afrikaner nationalism and British globalism came to a head on February 3, 1960. After a whirlwind tour of British-associated territories in Africa, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan delivered his famous “Wind of Change” speech in the South African Parliament in Cape Town: “The most striking of all the impressions I have formed since I left London a month ago is of the strength of this African national consciousness. The wind of change is blowing through this continent.” Macmillan then went on ungraciously to attack the racial policies of his host: “We reject the idea of any inherent superiority of one race over another. Our policy, therefore, is non-racial.”

Macmillan had promised to let Verwoerd see a copy of this speech beforehand so that the South African Prime Minister could prepare his own remarks. However, Macmillan’s chief goal was to score a PR triumph by embarrassing his host — the speech was broadcast over the radio — and refused to show him the text. Verwoerd, however, was a master of extemporaneous speech and debate. On the spot, and in his second language of English, he delivered a powerful plea for true racial justice:

The tendency in Africa for nations to become independent, and at the same time to do justice to all, does not only mean being just to the black man of Africa, but also to be just to the white man of Africa.

We call ourselves Europeans, but actually we represent the white men of Africa. They are the people not only in the Union but through major portions of Africa who brought civilization here, who made possible the present developments of black nationalism by bringing [the blacks] education, by showing them this way of life, by bringing in industrial development, by bringing in the ideals which western civilization has developed . . .

And the white man [who] came to Africa. . . has remained to stay. And particularly we in this southernmost portion of Africa have such a stake here that this is our only motherland, we have nowhere else to go. We settled a country [that was] bare, and the Bantu came in this country and settled certain portions for themselves, and [we believe in granting] rights for those people in the fullest degree in that part of southern Africa which their forefathers found for themselves and settled in.

But similarly, we believe in balance, we believe in allowing exactly those same full opportunities to remain within the grasp of the white man who has made all this possible.

In her diary, Verwoerd’s wife noted the impact of this speech on white public opinion: “The land rejoiced, the whites were proud, the Nationalists were elated. . . . In other regions in Africa too, the whites felt that here in South Africa is a man who can save the whites.”

Five months later, the reality of post-colonial Africa became brutally apparent in the aftermath of Belgium’s hasty withdrawal from the Congo. Whites were robbed, raped, and murdered in large numbers. Many found a new home in South Africa, where they were a living reminder of the folly of putting themselves at the mercy of black rulers.

There was an important political consequence to the public duel of prime ministers on February 3, 1960. By showing that adherence to Britain would mean continued pressure for racial integration, the exchange increased the vote for separation in the constitutional referendum that took place on October 5 of the same year. Like the “Remain” campaigners in the Brexit referendum, the opposition United Party predicted economic and political chaos from any weakening of ties with Britain or the Commonwealth, but 52.3 percent of white South Africans embraced the ideal of an independent republic for which Verwoerd had argued so fervently as editor of Die Transvaler. South Africa became a republic on May 31, 1961, 59 years after the old Afrikaner republics lost their independence at the time of the Treaty of Vereeniging in 1902.

Through this step, South Africa also left the British Commonwealth. Non-white nations such as India had been permitted and indeed encouraged to remain within the Commonwealth after adopting a republican constitution, and the Commonwealth mandate clearly excluded interference in the domestic affairs of members. Nevertheless, it was made plain to Verwoerd in London during a meeting of Commonwealth heads of government in March 1961 that South Africa’s continued membership was conditional on movement toward black rule.

Verwoerd chose national independence over subservience to the Commonwealth, asserting that “national pride and self-respect are attributes of any sovereign independent state.” Verwoerd returned home to a hero’s welcome at the airport in Johannesburg, where an estimated 60,000 supporters turned up to cheer the steadfast “man of granite,” as he came to be known.

Aftermath

To an unprecedented degree, Verwoerd succeeded in uniting the whites of South Africa behind a common purpose of self-preservation. This was a remarkable achievement after 150 years of Afrikaner-English strife. In March 1966, just five months before his murder, the National Party achieved its greatest electoral success, winning 58 percent of the total popular vote and making significant gains in the English vote. Clearly, Verwoerd could never have been removed by democratic means.

In the days following his assassination — his killer claimed to be “disgusted with the racial policy” — the unity of white South Africa found one last expression in a mass outpouring of grief. At one of the many memorial services held in both official languages across the country, a Reformed preacher paid tribute to Verwoerd: “His belief that God in his wisdom had created races and racial differences, so that each group could develop to the best of its ability within the confines of its own cultural tradition, was the transcending conviction of his life.”

It gradually became apparent, however, that there was no one of Verwoerd’s stature to take his place. Increasingly, each of Verwoerd’s three successors as Nationalist leader — B.J. Vorster, P.W. Botha, and F.W. de Klerk — fell short of Verwoerd’s “granite” will, yielding to a spirit of appeasement and, ultimately, capitulation. Unlike Verwoerd, these men did not defend Apartheid at home or abroad as the salvation of whites but excused it as a regrettable temporary necessity that could be discarded once the ignorant farmers of the Transvaal had been “enlightened” by the urban intelligentsia.

Verwoerd’s predictions about the fate of a white minority under black rule have been borne out since the ANC takeover in 1994. Likewise in Zimbabwe, the seizures of white farms and businesses — which have sent whites streaming out of the country — are just what Verwoerd would have predicted.

Legacy

Unlike many modern conservatives, Verwoerd acknowledged the biological reality of race and made it the core of his policy. However, he aimed neither to enslave nor oppress any other race. He sought only a free homeland for his own people, in exchange for homelands for blacks. Far from being a white “supremacist,” he avoided the language of white baasskap or “mastery,” used by his predecessor as Prime Minister, J.G. Strijdom, or rather he gave it an important twist: “Our [policy of] parallel development envisages mastery for the Bantu in his areas, just as we likewise envisage mastery for the white man in his own territory, with respect to his own people.”

I will close with one of Verwoerd’s most stirring speeches, delivered in 1958 at the Blood River in Natal on the holiest day of the Afrikaner calendar, the “Day of the Vow,” December 16. This commemorates the miraculous Battle of Blood River in 1838, when 470 Afrikaner Voortrekkers (“Pioneers”) defeated 15-20,000 Zulu warriors intent on exterminating them:

Whenever there is talk, as in Europe and also by some in our own land, that the solution of this conflict lies in the merger of all people — so-called integration — they don’t understand that this is not unification. All that will happen is the destruction of the white race. Not integration, but disintegration — disintegration of the white race, of the civilization and the religion that we have inherited — is the sole result. Therefore, even though we cannot trek any further, we say just like the Voortrekker of old: ‘We can still fight.’ And we will fight, even if we must perish, but we will keep fighting for the survival of the white man at the southern end of Africa and the religion that was given to him to spread here. And we will do it just as [the Voortrekkers] did: man, woman, and child. We will fight here for our existence, and the world needs to know it. We can do nothing else. We stand like Luther with the Reformation, with our back against the wall. We fight not for money or property. We fight for the life of our folk.

But we fight not only for our folk. I am deeply convinced in my heart that we fight for the survival of white civilization. . . . The white man at the southern end of Africa is an outpost of white civilization and as such the vanguard of the fighting mass, sent out ahead to the point where the first attacks must come. . . . Therefore we send the message to the outside world and we tell them, yet again, that there is only one salvation for the white race of the world. This is that whites and non-whites in Africa should each enjoy their own rights within their own territories.

Western nations failed to heed this message. Indeed, they helped crush the lonely Afrikaner outpost of white civilization. Today, every white nation faces the same threat of dispossession. This is our Blood River, our final stand. It’s time for our people around the world to claim Verwoerd as a hero and martyr of white survival, to honor his memory and to learn from him before it is too late.