‘Black Branding’ — How a D.C. Neighborhood was Marketed to White Millennials

Robert McCartney, Washington Post, May 3, 2017

Street crime in moderate doses doesn’t deter white millennials from swarming to take over traditionally black urban neighborhoods. On the contrary, they take pride in moving into an edgy, “authentic” community — and even brag about the violence.

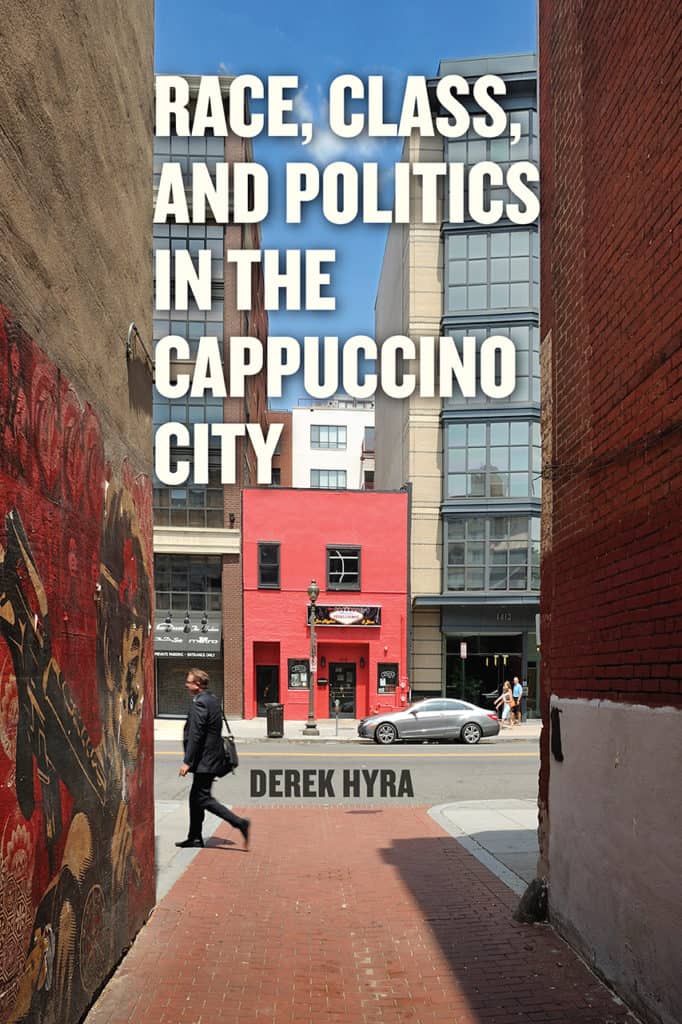

That’s what American University professor Derek S. Hyra argues in his new book, “Race, Class, and Politics in the Cappuccino City,” about gentrification in the District. At one point during his four years of field research in the Shaw/U Street neighborhood, he attended a local fundraiser where white recent arrivals seemed to boast about crime in their adopted neighborhood.

{snip}

The book raises an ominous warning about a cherished dream of District politicians and activists: that they can build neighborhoods that achieve harmony among diverse races and economic classes.

Instead, Hyra found that when mostly white millennials move into traditional African American communities, the two groups interact little and frequently chafe with each other.

For instance, the young, affluent newcomers tend to take over political and civic organizations and promote their own interests — a phenomenon on display in the recent explosion of bike lanes, dog parks and upscale coffee shops.

Many older, working-class blacks are able to remain, because of the District’s progressive affordable housing policies, and they welcome some benefits, such as a decline in crime.

But they also resent giving up both their former political influence and the character of their community. In one case, lobbying by new arrivals cost black churchgoers a long-standing convenience of parking in a school playground on Sunday mornings. Small, black-owned businesses that served as public gathering places have shut their doors.

{snip}

In one of the book’s most eye-opening chapters, Hyra casts light on a pair of phenomena — “black branding” and “living the wire” — that reveal a lot about racial dynamics in early 21st century America.

“Black branding” describes how developers and other mostly white business interests actively promoted Shaw’s historic black identity as a marketing strategy to attract white renters and buyers. Their success helped tip the neighborhood’s demographics from 70 percent black in 1970 to 30 percent in 2010.

{snip}

Hyra dubs a related trend as “living the wire” where whites in their 20s and 30s seek the titillation of living in a community with a hint of the urban grit of the Baltimore ghetto portrayed in the TV series “The Wire.”

{snip}

But while the groups share physical proximity, they remain isolated from one another in a pattern that Hyra calls “micro-segregation.”

The divisions break along more than racial lines. The neighborhood also has experienced frictions between conservative, religious residents and gays, and between upper-class and lower-class African Americans.

{snip}

What’s the solution? Hyra urges creating more “third spaces” like corner stores and recreation centers where all groups can feel comfortable. He also wants more funding for non-profits that encourage community cooperation and more subsidies for long-standing Mom-and-Pop businesses.

It’s not clear that such steps would be sufficient. But they would be necessary if the District is to fulfill its aspiration of seeing black and white, rich and poor, enjoy the city together.