Genes or Environment?

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, June 2010

Joseph M. Horn and John Loehlin, Heredity and Environment in 300 Adoptive Families: The Texas Adoption Project, Aldine Transaction, 2010, 209 pp.

The Texas Adoption Project (TAP) was one of the most thorough and long-running efforts ever undertaken to investigate the relative effects of environment and genes on intelligence and personality. It was a 35-year study of 300 families that had adopted children from the Methodist Mission Home of San Antonio, Texas. This slim, well-written book is the TAP’s final report.

Adoption studies are useful, of course, because they allow researchers to distinguish fairly easily between the effects of genes and environment. In an ordinary household, the parents provide all the genes of their children as well as the household environment, and egalitarians have long argued that environment counts for far more than genes; middle-class children do better than poor children, not because they inherited good genes, but because their fortunate parents gave them fortunate environments.

Because adopted children are genetically unrelated to their adoptive parents, they are natural study subjects: Do biological and adopted children growing up in the same family resemble each other because of their common family environment, or do the genes they inherited from different sets of parents play a more important role?

Many adoption studies have tried to answer this question, but the families in the TAP were particularly good research candidates for several reasons. First, the families were studied until the children, both adopted and biological, were adults. Most adoption research does not follow subjects for decades, so cannot determine if the relative importance of genes and environment changes over time. Another common defect in adoption studies is that little is usually known about birth parents, but a great deal was known about the TAP birth mothers. Unwed women who planned to give their children up for adoption lived at the Methodist Mission Home for some time before they had their babies. While they were at the home, they took a series of intelligence and personality tests. In some cases, a fair amount was also known about the birth fathers as well.

One disadvantage in the TAP, however, was that the average intelligence of the birth mothers was not that different from that of the adoptive parents. It is easier to separate the effects of genes and environment when there is a large IQ difference between birth and adoptive mothers, but the Methodist Mission Home operated in a way that tended to keep IQs similar. When a woman decided to enter the home, both her parents and the parents who planned to adopt the baby were expected to share the costs of room, board, and medical treatment. This meant that birth and adoptive mothers both tended to be middle class. However, there was a considerable range in intelligence and personality in both groups, so it was possible to see if placing a child from a less intelligent mother in a home with intelligent adoptive parents would raise the child’s intelligence — or vice versa. Many of the families also had biological children, so it was possible to see whether being reared in the same family made children similar to each other even if they were not biologically related.

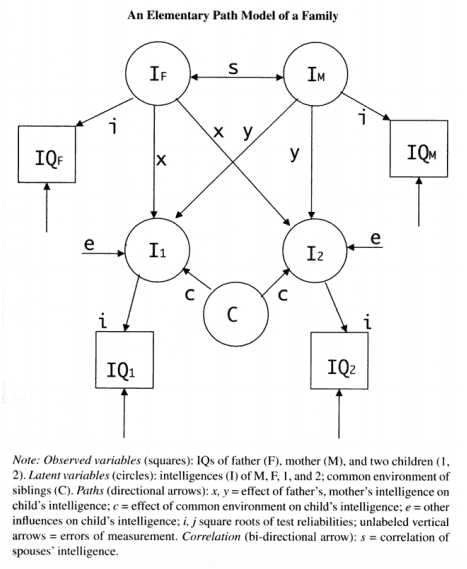

The method used in the TAP to analyze the effects of genes and environment was the path model. The figure on this page is an example of a path model for a typical family of two parents and two children. The caption under the figure explains the model. Squares are observed variables, that is to say, values that can be measured. In this case, they are the tested IQs of the mother and father (IQM and IQF) and of child 1 and 2 (IQ1 and IQ2). The researcher tries various values for the contributions of genes and environment to the children’s intelligences, and chooses the model that best explains the observed variables.

The trouble with this model is that parents give children both genes and environment. The causational paths of x and y, that is to say, the influences of the mother and father on the intelligence of the children, includes both, and there is no good way to separate them.

This figure shows the path model the researchers used in the TAP, which plots the genetic and environmental influences in a family of two parents, their two biological children, and two adopted children, each with his own set of parents. Sophisticated modeling of this kind — it is not necessary fully to understand the model but the caption offers a reasonably good explanation — lets scientists separate out the effects of genes and environment.

The findings of the TAP are in line with many other studies: Genes count for a great deal more in the development of intelligence and personality than family environment. If anything, the TAP results suggest that growing up in the same family can make people less like each other, as they establish personalities to distinguish themselves from each other. Finally, family environment has some effect on intelligence when children are young, but drops essentially to zero by the time children become adults.

Parents are often astonished to learn that although genes account for perhaps one half or more of the variation in the intelligence of their children, the remainder is almost certainly not the result of the environment the parents provided. When children grow up in the same family they have what is called a shared environment — the same parents, house, neighborhood, etc. — and a non-shared environment, which is all the unique things that happen to them and to no one else. Path modeling of the kind used in the TAP makes it possible to distinguish between the effects of shared and non-shared environment, and what children have in common doesn’t seem to have much effect on the way they turn out. Living in the same household doesn’t appear to influence children nearly so much as the unique experiences they have on their own.

It would be wrong, however, to conclude that households have no effect. Adoptive families do not represent the entire range of all families, since agencies do not place children in indigent or obviously abusive homes. No doubt, children who grow up in complete misery and squalor suffer because of this, but within the broad range of the middle classes, the effect of household environment on intelligence is small for children, and drops to nothing for adults.

The TAP found that correlations in intelligence and personality were greater between fathers and their children than between mothers and children. The authors could give no explanation for this, but whatever the cause, it does not support the view that environment overwhelms genes. Mothers usually spend more time with children than fathers do, so their environmental effect should be greater.

One of the TAP’s most intriguing conclusions concerns the manner in which personality is, or is not, influenced by family environment. When parents (both birth and adoptive) and children were compared on the results of personality inventory tests, the correlations were closer between birth mothers and their adopted-away children than for parents who reared their biological children themselves. In other words, the children whose personalities were most like that of their mothers’ were the ones who never knew their mothers. As the authors note, “The suggestion is that processes like imitation and identification, which would tend to lead to positive correlations, are being outweighed by processes like contrast or competition, which would lead to negative ones.” Children may be developing their personalities in opposition to their parents rather than in conformity with them.

The TAP reached other conclusions that are in line with other studies: About one quarter to one half of differences in personality are due to genes and the rest to unshared environment. Over time, however, children do develop personalities that tend to resemble those of their parents. Perhaps genetically-based similarities become more evident after a child moves out and is no longer trying so hard to be different from his parents. Not surprisingly, the adult personalities and IQs of unrelated people growing up in the same household have a correlation of zero.

The TAP offered an interesting opportunity to study what is called genotype-environment correlation, which assumes that parents provide environments for their children that match the parents’ genotypes. For example, high-IQ parents are likely to surround their children with books and educational games, thus giving them an IQ-boosting environment in addition to good genes. Low-IQ parents would presumably do the opposite, so that genes and environment work together to push children toward extremes.

Adopted children are genetically unrelated to the parents so genotype-environment correlation should presumably have less effect on them, leaving adopted children, as a group, with less variation (a smaller standard deviation) in intelligence and other traits. The TAP found no such results with, if anything, a tendency towards a smaller standard deviation in biological children. Allegedly IQ-modifying environments did not have much effect at all. However the TAP results are analyzed, they run directly counter to what has been an article of leftist faith for decades: that privilege, not genes, accounts for success.

The authors of the study point out, however, that unshared environment (and measurement error) account for a great deal of individual variation, and this means that much remains unexplained. What is it about the unshared environment that accounts for 30 to 40 percent of individual variation in intelligence and personality? The authors suspect that as techniques for measurement and observation improve, it may be possible to find out how individual, unique environments act on individual genotypes, but warn that knowledge at this level may come at an unacceptable cost in privacy. It would probably require intrusive techniques to find out how unshared environment really works.

Finally, the authors note that their calculations for the genetic influence on variations in intelligence — 25 to 35 percent rather than 60 percent or so — are lower than those often found in studies of identical twins reared apart. They explain this by describing the difference between additive and nonadditive effects. Additive effects are the cumulative result of genes acting individually, whereas nonadditive effects arise from configurations or combinations of genes. Examples of the latter would be of dominant and recessive genes, in which the effect arises not just from the presence of genes but from how they combine with each other. Another non-additive effect is called epistasis, which results from genes acting together in ways that go beyond whatever effect each would have had individually.

Because identical twins have identical genotypes, they share both additive and nonadditive effects, so the influences of genes and environment are clear. Ordinary siblings have unique gene combinations in which nonadditive effects work in unpredictable ways. These effects tend to make siblings different from each other or from their parents — thus giving the appearance that genes were playing a smaller role — but these very differences arise from nonadditive genetic effects and are therefore the result of the action of genes.

This study did not have a racial angle. All the parents and children were white, so no formal conclusions can be drawn from it about whether growing up in a white family would raise the IQs of black children. Nevertheless, the implications are clear. The environment parents provide for their children has surprisingly little influence on how they turn out, and may even push children to become less like other family members because of competition or the desire to be different. This effect would surely be greater in families — whether biological or adoptive — composed of people of different races.

Perhaps the greatest value of this study for non-specialists, however, is the clear way in which it describes how the research was carried out, and the many steps taken to ensure the most accurate results. The authors explain a host of details, whether about statistical methods or practical matters, that bring their story to life. This is the kind of science egalitarians hate, but the TAP was conducted with such obvious care, rigor, and dispassion that it should be convincing to all but the most crazed ideologues.