Civil Rights Under Ronald Reagan

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, July 1992

Civil Rights Under Reagan, Robert R. Detlefsen, ICS Press, 1991, 237 pp.

The enforcement of civil rights laws has been one of the most amazing frauds ever perpetrated on the American people by its own government. Laws that were passed to forbid racial discrimination have been turned completely inside out and are now used to require the very behavior they were written to prohibit. How could this have happened?

Robert Detlefsen, an assistant professor of political science at California State University, has written a fascinating and brilliant account of how the very notion of “civil rights” was stood on its head. He shows, case by case, how the Supreme Court, almost single-handedly, twisted the law to suit its own political views.

Because the media and the academic bureaucracy have generally held the same political views, there have been very few accounts of this subversion of the law that were not transparent attempts to justify it. Prof. Detlefsen’s book is therefore one of the first to combine a fine legal mind with a proper sense of outrage at the violence that has been done both to the law and to simple notions of justice. It is an indispensable volume for anyone who wishes to know how “equal opportunity” was transformed, legally, into “affirmative action.”

Civil Rights Under Reagan is ostensibly about a Republican president’s attempts to undo that transformation, about how his appointees in the Justice Department tried to dismantle race-based preferences and return to the color-blindness that had been Congress’ intent. The book certainly tells that story, but in so doing, it tells the more important story of how President Reagan’s men were defeated by a Supreme Court that was determined to sacrifice the Constitution to its own views of race.

The Act of 1964

As Prof. Detlefsen makes clear, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was unequivocal in forbidding racial discrimination in employment practices. One can argue that in a free country, an employer should have the right to choose his employees for whatever reasons he likes, racial or otherwise. Congress did away with that freedom, but it went no further. It specifically denied that employers were required to use racial preferences to make up for imbalances in their work forces, and it specifically permitted employers to use standardized employment tests so long as their purpose was not racial discrimination.

Contrary to popular mythology, it was not President Johnson but President Nixon who first violated the principle of color-blindness. It was the “Philadelphia Plan” established in 1969, that first required employers — in this case, Philadelphia construction companies doing government work — to set non-white hiring quotas. There was strong opposition to this both in Congress and within the administration, but Attorney General John Mitchell, hardly a name associated with liberal derring-do, ruled that the plan was legal.

Prof. Detlefsen points out that by forcing companies to hire by race, Attorney General Mitchell had repealed an act of Congress, passed only five years previously, that forbade precisely that. Any ordinary student of American government would here expect the Supreme Court quickly to rule against the administration. Instead, as soon as it got the chance, the Court broadened racial preferences.

Griggs v. Duke Power

The chance came two years later, in 1971. The Duke Power Company had a special training program that was open only to high school graduates who had scored well on a standard intelligence test. Applicants of all races had to meet the same requirements. However, since blacks were more likely to do badly on the intelligence test and to have left school without a diploma, the Supreme Court ruled that the requirements were racially discriminatory. Thus was born the famous “disparate impact” rule, whereby race-neutral job standards could be thrown out if non-whites were less likely to measure up to them.

Once more, a law passed by Congress was neatly sidestepped. Congress forbade job requirements intended to discriminate; the Court did away with intent and forbade standards that had what it called discriminatory effect. This was a huge difference, because there is virtually no test or qualification for a job by which whites do not surpass blacks.

In the Griggs case, the Court ruled that only employers who had, in the past, practiced racial discrimination (Duke Power apparently had done so before 1964) had to worry about “disparate impact,” but this limitation disappeared almost immediately. By 1972, it was illegal for any employer to rule out potential employees who had arrest records, since this had a “disparate impact,” that is to say, blacks were more likely to have arrest records than whites.

Thus began the horror that has plagued employers ever since: what is a legitimate job test or hiring standard and what is discrimination? Eleanor Holmes Norton, now the non-voting congressional delegate from the District of Columbia, was one of Jimmy Carter’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commissioners in the 1970s. At the time, she explained that there was a simple way for employers to figure out whether their hiring practices were free of disparate impact: make sure that they hired a lot of blacks. Any company that did not might be the target of a law suit.

Connecticut v. Teal

Just how far the concept of “disparate impact” could be taken became clear in the 1982 case of Connecticut v. Teal, in which the Reagan Justice Department suffered one of its many defeats. The state of Connecticut used a written test to determine which employees in its welfare department would be eligible for promotion. The state knew very well that it could not simply give the test and promote the people with the top scores, because they might all be white. Therefore, it lowered the passing score from 70 to 65, so as to open the door to more blacks.

Still, only 54 percent of blacks passed, whereas 80 percent of whites did, with the result that 206 whites and 26 blacks passed. Whites had higher average scores than blacks, but even if the state had ignored the scores and made proportionately equal promotions by race, only five of the 46 employees who were eventually promoted would have been black. The state doubled that number — at the expense of whites — and promoted 11 blacks and 35 whites.

To the layman it would appear that it was whites who had been disadvantaged, and who would have reason to sue. In the upside-down world of civil rights law, it was blacks who sued. Blacks who failed the test — despite the lowered passing score — claimed that they had been unfairly deprived of an opportunity for promotion because of the test’s disparate impact.

The Reagan Justice Department opposed the case, but on the mildest grounds. It agreed that the test had had a disparate impact but pointed out that this had been compensated for by the jiggery-pokery afterwards that resulted in a disproportionate number of promotions for blacks. Thus, the case turned on whether the entire selection process, which had not had a disparate impact, was discriminatory because one stage of it had a disparate impact.

The black plaintiffs won, thus establishing the rule that preferential treatment of blacks was still not good enough if, at any point in the selection process, disparate impact could be detected. This was a stunning setback for fairness and common sense, but the decision was met with jubilation in the press, and the Reagan Justice Department was tarred as racist and reactionary for having been on the “anti-civil rights” side.

The Justice Department tried something bolder in the case of a systematic racial preferences program established in 1981 by the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) to correct alleged but unproven “discrimination.” It argued that the Civil Rights Act provides for race-based hiring preferences only as a remedy for victims of past discrimination. The NOPD plan completely ignored the past, and handed out benefits to blacks just because they were black.

In Williams v. New Orleans, the Court of Appeals simply brushed aside the Justice Department’s argument. Despite a clear request to explain itself, it gave no legal or moral justification for an affirmative action program that gave benefits to blacks who may not have suffered discrimination, and punished whites who may not have been guilty of it.

Johnson v. Transportation Agency

The impulse to discriminate against whites was soon directed against men. The most definitive example of this was the 1987 case of Johnson v. Transportation Agency, in which Santa Clara County (CA) was allowed to promote a less qualified woman over a man simply because there were fewer women than men at the supervisory level. Once again, there was no evidence that the imbalance of men was due to discrimination or that women had even wanted those jobs in the past. As Prof. Detlefsen explains, what makes the case interesting is that the Supreme Court made explicit something that had always been implicit but never spelled out: “that a statistical imbalance favoring white males as a group is in itself sufficient to justify employment discrimination against individual members of that group.”

The Supreme Court.

Justice John Paul Stevens openly admitted in his Johnson opinion that in approving race and sex preferences, he was flouting the will of Congress, which had explicitly forbidden such preferences. Prof. Detlefsen wonders if this is not “the most forthright admission of judicial malfeasance ever made by a sitting justice.”

The cumulative effect of cases like these was enormous. The Griggs, Teal, and Johnson cases established that “discrimination” was not a matter of malicious intent but of numbers, or what came to be called “underutilization” of minorities or women. The entire thrust of “civil rights” litigation changed. It was not necessary to prove intent to discriminate or to find actual victims of discrimination. Any company that had not voluntarily discriminated against whites so as to have enough non-white employees, could be forced to discriminate against them.

As the definition of “discrimination” changed, so did the remedies for it. The courts have a long history of requiring restitution to someone who has been wronged. Nevertheless, restitution has always been to injured individuals. Once the notion of discrimination had been stripped of both intent and of identifiable victims, restitution had to be made to a race. If a company were forced to give blacks preferential treatment because of “underutilization,” the beneficiaries were not being compensated for past wrongs. They were reaping windfall benefits because they happened to be black at a time when blacks as a race were getting preferences.

Prof. Detlefsen explains that the notion of group punishments and group rewards is a radical departure from the principles of the Constitution, which is deeply concerned about individual rights but says nothing about group rights. Even the Supreme Court justices who sanctioned this revolution had some notion of what they were doing. Justice Lewis Powell once wrote, “As part of this nation’s dedication to eradicating racial discrimination, innocent persons may be called upon to bear some of the burden of the remedy.” In what other branch of the law would a judge blithely admit that he was prepared to punish the innocent? This is all the more astounding, because when it comes to robbery or murder, the liberals who support affirmative action happily quote Sir William Blackstone: “It is better that ten guilty persons escape than one innocent suffer.”

Race and the Schools

Once segregated schooling was brought to an end with the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education, definitions of school desegregation went through as great a change as definitions of discrimination. The original Brown case was about ending forced racial separation in schools. Prof. Detlefsen recounts how the goal of the courts quickly became the quite different one of bringing about forced racial mixing in schools. Mandatory busing was the means to bring this about. Whereas, in the past, children might have been prevented from attending certain schools because of race, they were now obligated to attend certain schools because of race. Supreme Court Justices decided that racial mixing was such a desirable goal that they would force it on schools that had never been legally segregated to begin with.

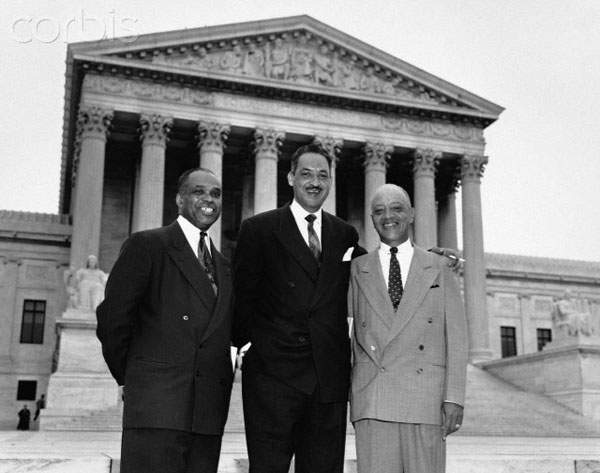

George Hayes, Thurgood Marshall, and James Nabrit, Jr. after their victory in Brown v. Board of Education.

Prof. Detlefsen also tells the less well known story of the Reagan Justice Department’s battle with the Internal Revenue Service over tax-exemption for schools. At the time, the IRS was doing everything within its power to crush the so-called “segregation academies” that appeared in response to forced integration.

The Agency’s zeal for this task was behind its attack on Bob Jones University of Greenville (SC). Bob Jones was a private, Christian school that did not have a racially discriminatory admissions policy. However, its administrators had found what they took to be biblical injunctions against interracial dating and marriage, and forbade this to their students on pain of expulsion. In 1976, the IRS officially revoked the university’s tax-exempt status, retroactive to 1970. The university appealed the revocation to the Supreme Court, where the Reagan Justice Department argued in its favor. The university lost.

In deciding Bob Jones University v. United States, the Supreme Court almost entirely ignored what the case was about. In their majority opinion, the Justices roared about “racial discrimination in education,” and the “shackles of the ‘separate but equal doctrine’” as if Bob Jones had put up a big sign on its admissions office that said “No blacks need apply.” In fact, the university was a voluntary association of like-minded people who happened to read the Bible in a particular way. Moreover, a ban on interracial dating is not “discriminatory” since it affects all races. There was no law that applied to what the university was doing, which was why the Court had to act as if Bob Jones were doing something illegal. It seems that the justices simply did not like the ban on interracial dating and decided to punish the school because it had one.

As Prof. Detlefsen points out, the effect of this decision was to give huge powers to the bureaucrats at the IRS. What was to stop them from attacking any school that took an unconventional position? Could a school lose tax exemption for teaching libertarianism or Marxist revolution? Presumably so, if the Supreme Court could be made to feel strongly enough about it.

The string of defeats the Reagan Administration suffered at the hands of the Supreme Court is sad enough, but perhaps saddest of all was its defeat at the hands of American businessmen. There was one form of affirmative action that was wholly within the President’s power to abolish. This was what had begun with the Philadelphia Plan, the Department of Labor’s requirement that government contractors practice racial hiring preferences. The requirement could have been revoked by executive order, and in 1985, the administration let it be known that it was considering doing so.

It is important to note that government contractors were not going to be prevented from practicing affirmative action voluntarily; they were simply to be relieved of the obligation of doing so. This did not stop the press and civil rights groups from acting as if Ronald Reagan were about to stand at the school door with an ax handle. That was to be expected. The surprise was that the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) strongly opposed relaxing the requirement.

Why would they want obligatory racial preferences rather than voluntary preferences? The reason is that so long as they were obligatory, disgruntled whites were essentially prevented from claiming reverse discrimination. As soon as preferences became optional, whites would be in a much stronger position to file discrimination suits.

Then why not abandon affirmative action entirely and hire strictly on merit? Most NAM members are large companies with well entrenched affirmative action bureaucrats who would make a fearful din if they were fired or reassigned. Often these people are black, and if affirmative action were abandoned they could call down the wrath of the civil rights industry in the form of boycotts, protests, and who knows what else.

There was another reason why NAM preferred the status quo. Its members have already hired the head-hunters and head-counters necessary to comply with government-mandated racial preferences. Small companies, which were generally in favor of lifting affirmative action requirements, often have not. The overhead of discriminatory hiring and racial paperwork is therefore a greater burden for small companies than for big ones, and this gives big companies an advantage. NAM mounted so much opposition to the idea of lifting discrimination requirements that the government backed down.

Prof. Detlefsen’s book is full of such illuminating and disappointing stories. He writes, for example, of the two Carter-appointed Civil Rights Commissioners who, in 1984, wrote that civil rights laws were not passed to protect white men. He writes of how the Supreme Court decided that consent decrees were not court orders, thereby circumventing the law and stopping 51 Justice Department suits in their tracks.

Since Prof. Detlefsen clearly sees the folly in what the courts have done, he even speculates about what could have motivated them. He argues that of the three branches of government, the judiciary is most vulnerable to intellectual fashion. The fashion that dictated one disastrous ruling after another is what Prof. Detlefsen calls the civil rights ideology. In its pure form, all white men are seen as the oppressor class, and all non-whites and women are the oppressed class. Civil rights are therefore not a means of securing legal equality but of liberating the oppressed. Supreme Court Justices may properly violate the Constitution and ignore the law in the name of this vital task.

Prof. Detlefsen also sees no coincidence in the fact that the whites who enforce affirmative action are men well established in their careers, who will never suffer the sting of discrimination. He has little sympathy for the likes of Senators Joseph Biden and Edward Kennedy, who promote self-righteous policies at no cost to themselves or to their families.

Civil Rights Under Reagan is a thoroughly worth-while book. Prof. Detlefsen’s research is meticulous, his reasoning clear, and his examples convincing. Some of Prof. Detlefsen’s arguments are subtle, and he makes no concession to readers who do not stay alert, but these are only advantages to anyone willing to give this book the close reading it richly deserves.