The Great Replacement: Indianapolis

Gregory Hood, Paul Kersey, and Henry Wolff, American Renaissance, May 23, 2020

Indianapolis is known as the “Crossroads of America.” It hosts the world’s largest one-day sporting event, the Indy 500. It was one of the great capitals of the Midwest, and as “Railroad City,” it was a hub that joined the continent. Its magnificent “Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument” is a neoclassical tribute to the common men who fought to turn America into a superpower. It exemplified what America once was.

Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Indianapolis, 1900. Credit: Album / quintlox

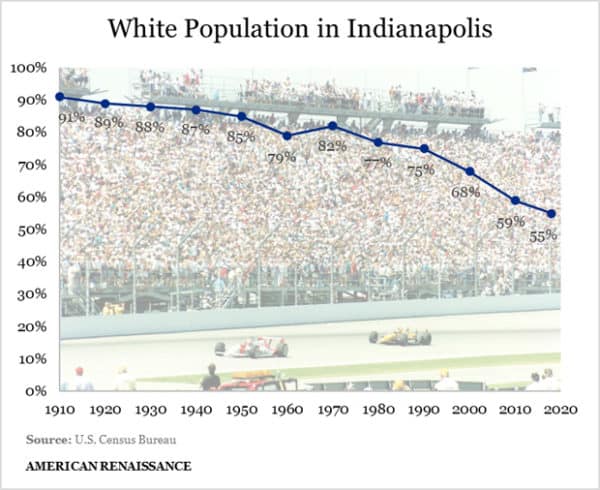

Today, Indianapolis represents what America is: a declining city with a shrinking white majority, collapsing culture, and rising racial tensions. In 1910, Indianapolis was 91 percent white. It retained its white supermajority until about 1990, when about a quarter of its residents were non-white. Whites dropped below 70 percent by 2000, and crime rose dramatically. Today, the white population has dipped to just 55 percent. And Indianapolis has been the backdrop for horrific crimes.

During the Civil War, Indiana governor Oliver P. Morton was a ferocious opponent of the Confederacy who trampled constitutional norms and supported Radical Reconstruction. Indiana was a pillar of the Republican coalition that dominated American politics from after the Civil War to the Great Depression.

Indianapolis was a stop on the Underground Railroad and had a permanent black population. The Indianapolis Freeman, the first illustrated black newspaper in America, was published from 1888 to 1926.

Indiana was a stronghold of the middle-class, “second-era” Ku Klux Klan. The KKK elected a governor and “dominated” Indianapolis politics in the 1920s. The Klan rose to power along with an increase in the black population. From 1910 to 1920, the number of blacks rose from 21,816 to 34,678, or 59 percent. By 1930, there were 43,967 blacks.[1] The Indiana Klan collapsed after “Grand Dragon” D.C. Stephenson raped and murdered a white woman. A movement dedicated to Christian morality and cultural conservatism could not survive that level of hypocrisy and evil.

In 1930, one social worker estimated that 90 percent of Indianapolis blacks, many of whom were recent arrivals from the South, worked in unskilled jobs.[2] One notable exception was “Madam” C.J. Walker, who became the first self-made female millionaire in the United States — of any race — by selling hair products. She’s the subject of a documentary airing on Netflix. Indiana Avenue, the “Hoosier Harlem,” became the center of a thriving jazz and blues scene, with more than 25 jazz clubs by the mid-1930’s.[3] Remnants of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association observed the UNIA’s founding with a parade in 1931. [4] Whites and blacks were mostly segregated, and there was a black community with its own institutions.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, blacks switched their loyalty from the Republicans to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Democrats. During the Depression, some blacks used the Garveyite tactic of setting up self-sufficient black cooperatives, while others organized to get jobs from white employers.[5] From 1935 to 1938, the federal government built the Lockefield Gardens apartment blocks exclusively for poor blacks. Many city officials opposed the project. White union workers wanted the construction jobs, and fought hard against federal demands for a racial quota of black workers. It may be a surprise for some to learn that Washington was already requiring this sort of thing in 1935. Local officials ignored the quota.[6]

During the 1940s, segregation began breaking down, and In 1949, Indiana repealed its law that allowed segregated school districts. Blacks began settling in the suburbs, and many whites moved away.[7] When blacks moved out of their historic neighborhoods, Indiana University moved in, using eminent domain to take land. Highway construction also broke up black neighborhoods. NewAmerica.org calls the process “The Ethnic Cleansing of Black Indianapolis,” but it was what happened in most Northern cities: With integration and blacks moving out, black neighborhoods lost their cohesiveness. Whites moved away from blacks, and integrated neighborhoods declined.

Indianapolis had an especially bitter fight over school desegregation. In 1970, what was known as the “Unigov” policy merged several communities into one larger city, making Indianapolis more powerful and important. However, this conglomeration did not include the school systems. Smaller communities didn’t want to lose control over their local schools; white parents didn’t want integrated schools. In 1971, federal judge S. Hugh Dillon ruled that Indianapolis Public Schools were guilty of practicing segregation and ordered forced busing. Thus began two remarkable decades during which the same judge supervised the racial balance in schools, ruling in 1997 that his initial order would be “continuing and permanent.”

The result was predictable. By the time forced busing finally ended in 2016, Indianapolis’s schools were more segregated than they were at the beginning. “Nearly all of the students in Indianapolis Public Schools today, 74 percent, are black or Hispanic,” wrote The Atlantic in 2016. “Most of the students, 71 percent, are poor enough to qualify for meal assistance.”

Whites left the city to escape integrated schools. From 1980 to 2018, the white population dropped from 77 percent to 55 percent. The diverse Indianapolis of the new century has seen more crime; from 2011 to 2019, the city got more homicides every year. A public affairs lecturer at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis blamed food insecurity, housing struggles, unemployment, and drug abuse. The Indianapolis Star tried to “explain Indianapolis’ homicide problem” in 2018. It answered the questions, “Who is being killed?” (mostly young black males) and “How They’re Being Killed” (with guns). It did not answer the question, “Who is killing them?”

Unfortunately, neither do police reports from 2017 or 2018. We get a lovely racial breakdown of the police department itself, but not of suspects. Earlier years aren’t online. A 2015 report from RTV6 did note that “black men’s killers tended to look like them.” A Indianapolis Star report from that same year found that 80 percent of homicide victims and 82 percent of suspects had criminal records.

2015 was not just a record year for murder in Indianapolis. There were three infamous black-on-white crimes. In November, three blacks entered Amanda Blackburn’s home. She was pregnant. They raped her and then one shot her. Luckily, her 15-month-old son was in a crib upstairs and wasn’t harmed. Two suspects accepted a plea deal to testify against alleged killer Larry Taylor. Mr. Taylor reportedly shot her in the back of the head, leaned over her, looked her in the face, and watched her bleed. Mr. Taylor also murdered a Mexican man and raped a woman at gunpoint a few days earlier. He will go on trial this July, almost five years later. Mrs. Blackburn’s husband, a pastor, has written a book about forgiveness for the killers. Mr. Taylor’s defense team may use the book at trial.

In December that year, black teenager Cameron Tibbs shot and killed white man David Bowman at a gas station. Mr. Tibbs turned himself in a few days later. He was indicted for murder, but was granted bail. Police then arrested him for robbing a pharmacy. In November 2016, a jury found Mr. Tibbs not guilty of murder, but convicted him of carrying a handgun without a license and obstructing justice.

Also in December 2015, Ronald Exantus, a black man from Indianapolis, drove to Versailles, Kentucky (a place he had never been), broke into six-year-old Logan Tipton’s house, went to his bedroom and stabbed him to death. He also stabbed Logan’s father and two older sisters but did not kill them. Versailles, Kentucky is more than 96 percent white, and the family had left the door unlocked. In 2018, a jury found the killer “guilty but mentally ill” for stabbing the father and two sisters, but found him not guilty by reason of insanity for killing the boy.

These cases are already forgotten, but others not. On April 9, Indianapolis police officer Breann Leath died after she was shot answering a call to a domestic disturbance along with two other officers. A mother of a three-year-old and just 24 years old, she was black, as is her accused killer. She was given a formal sendoff at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, while hundreds of officers saluted and with 1,900 people watching a live broadcast.

One case looked like it might matter. Angela Summers was a white postal worker. Late last month, an Indianapolis man shot and killed her on her route. There was brief interest on social media but when the suspect turned out to be a black man, the case faded. Coworkers released balloons into the air for her, and that was the end of it.

On May 6, Indianapolis man Dreasjon “Sean” Reed, who was black, live-streamed a police car chase. He stopped the car and ran, as he swore at someone telling him to stop, presumably the police. Police say that there was an exchange of gunfire. The officer who shot him was also black. There were mass protests. Comedian Mike Epps denounced the killing. The Source wrote, “21-year-old Sean Reed was murdered at the hands of the Indianapolis Police Department following a high-speed chase.”

Concerns about social distancing faded, and protesters thronged the streets, chanting “black lives matter” and screaming for “justice.” There was outrage about an officer’s tactless comment immediately after the shooting: “I think it’s going to be a closed casket, homie.” He has been suspended; his race is unknown.

Just hours after Mr. Reed died, 19-year-old McHale Rose called police to report a burglary. When they responded, he opened fire and ambushed them. They returned fired and killed him. He was black. Maybe he wanted revenge for Mr. Reed. Just this month — in a single week — the department got 26 threats against officers.

In another recent case, police officer Jonathon Henderson, a 22-year veteran, accidentally hit and killed Ashlynn Lisby as he drove to work. There’s no evidence that this wasn’t just a terrible accident. Lisby was a 23-year-old single mother with three children, who was pregnant. She had reportedly “struggled with homelessness.” She would seem to be a sympathetic figure, but she was white, so who cares?

While I was writing this article, Indianapolis police responded to three shootings in two hours. The night before, an unidentified man was shot dead. Before the coronavirus, the city was on pace for another record year for homicides. Yes, Indianapolis has changed.

Governor Morton, who wanted to lay waste to the South through reconstruction, is one of the people honored along with George Rogers Clark and William Henry Harrison at the “Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument.” If he could see his fallen capital today, would the old Radical still think it was worth it?

* * *

[1] Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century, by Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana University Press, 2000. P. 36

[2] Ibid, 37.ˊ

[3] Hoosiers and the American story, by Madison, James and Sandweiss, Lee Ann., Indiana Historical Society, 2014, p. 221

[4] Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century, by Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana University Press, 2000. P. 77

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, 85.

[7] Moving on Up: The Experience of Post World War II African Americans of Indinapolis, by Kyle Huskins, Indiana University, March 2019, p. 22