(Minerva Teichert, ca 1950-51; LDS.org)

John W. Welch, et al., eds. Knowing Why: 137 Evidences That the Book of Mormon Is True (American Fork: Covenant Communications, 2017), 314-318, treats Alma’s famous exclamation “O that I were an angel”:

I was especially struck by these paragraphs:

Alma’s use of trumpet imagery is interesting in light of the timing in which he wrote this thoughtful and moving piece of prophetic poetry—the 16th year of the reign of the judges. This was the 49th year since King Benjamin’s powerful oration at the coronation of his son Mosiah, an event some scholars believe was a jubilee celebration.

Christopher Wright explained, “The year of jubilee came at the end of the cycle of 7 Sabbatical Years.” Terrence L. Szink and John W. Welch documented, “The jubilee text of Leviticus 25 compares closely with two sections of Benjamin’s speech.” If this was a jubilee year, then Alma stepped down from the judgment-seat and began his missionary activities in the 42nd year, or the sixth sabbatical year, and Alma 29, marking the closure of one period in Alma’s ministry and beginning of a new, marks the next jubilee year.

In the 49th year, on the Day of Atonement, the “trumpet of the jubilee” would have again been sounded, “throughout all [the] land” (Leviticus 25:9), heralding in the next jubilee year. The Hebrew word yobel (carried into English as jubilee) literally means trumpet.

In the land of Israel, the trumpets would probably have been rams horns, but other kinds of horns could have been used, and some scholars have argued that loud shouting could also suffice. Alma’s expressed desire to “speak with the trump of God” and “with a voice of thunder” (Alma 29:1–2) thus seems “especially appropriate in this second identifiable jubilee season in Nephite history.” (314)

Textually, it is remarkable, to say the least, that the Book of Mormon manifests literary motifs associated with the jubilee in two places exactly 49 years apart. The rapid dictation of the Book of Mormon would hardly have allowed time for Joseph to count off the years and to mark these jubilees with such subtle sophistication, let alone to set the gorgeous language in Alma 29 so richly in this contextual background. (315)

But re-reading Alma 29 also reminds me of a column that I published in the Deseret News back on 20 June 2013:

“Intertextuality” is a word used to describe ways in which various texts refer to, or play off of, each other, often without explicitly indicating it. For example, a 2012 book titled “Seven Habits of Highly Fulfilled People” unmistakably alludes to Stephen Covey’s famous 1990 best-seller, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.” Sometimes, authors hope that their audiences will keep the other text in mind.

The Book of Mormon contains numerous such examples, and probably quite a few remain to be discovered. John Welch has shown that legal language in the Book of Mormon tends to be highly consistent, perhaps indicating its dependence on underlying legal materials. Royal Skousen’s superb studies of the book’s textual history have established what he calls its “systematic nature”; its terminology and phrasing tend to be very consistent. I offer three non-legal examples first discussed by Professor Welch:

In Alma 36, Alma describes his conversion. At one point, he reports, “methought I saw, even as our father Lehi saw, God sitting upon his throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels, in the attitude of singing and praising their God” (36:22). Twenty-one of these words are quoted verbatim from 1 Nephi 1:8, where Lehi “thought he saw God sitting upon his throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels in the attitude of singing and praising their God.” These two passages are far apart. Yet, as Professor Welch points out, it’s “highly unlikely that Joseph Smith asked Oliver Cowdery to read back to him what he had translated earlier so that he could get the quote exactly the same. If that had happened, Oliver Cowdery would undoubtedly have questioned him and lost faith in the translation.”

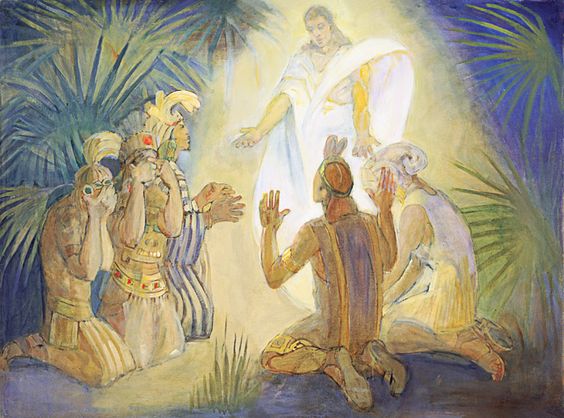

Similar instances occur when, in Helaman 14:12, Samuel the Lamanite plainly quotes 21 words from King Benjamin (see Mosiah 3:8), and, very likely, when 3 Nephi 8:6-23, recounting the destruction in the New World at the crucifixion of Christ, mentions precisely the same natural phenomena prophesied by Zenos in 1 Nephi 19:11-12.

I would like to suggest two additional illustrations of Book of Mormon “intertextuality” that I, at least, don’t recall being mentioned anywhere else.

The first concerns Alma 29:1-2, in which Alma the Younger famously expresses his yearning to reach all humanity with the message of the gospel:

“O that I were an angel, and could have the wish of mine heart, that I might go forth and speak with the trump of God, with a voice to shake the earth, and cry repentance unto every people! Yea, I would declare unto every soul, as with the voice of thunder, repentance and the plan of redemption, that they should repent and come unto our God, that there might not be more sorrow upon all the face of the earth.”

Alma’s expression of his desire seems plainly based upon his own personal conversion experience, in which an angel appeared to him who “spake as it were with a voice of thunder, which caused the earth to shake,” and summoned him to repentance. “Doth not my voice shake the earth?” the angel asked, rhetorically. “He spake unto us, as it were the voice of thunder, and the whole earth did tremble beneath our feet” (see Mosiah 27:10-15; Alma 36:6-11).

The second proposed example suggests reliance upon the Old Testament story of Elijah, presumably available to the Nephites via the brass plates that Lehi brought with him from the Old World. (John Sorenson, incidentally, has suggested on other grounds that the brass plates originated in the northern kingdom of Israel, where Elijah lived and prophesied.)

In 1 Kings 19:11-12, we read of Elijah’s experience in the wilderness (perhaps in the Sinai) that “the Lord passed by, and a great and strong wind rent the mountains, and brake in pieces the rocks before the Lord; but the Lord was not in the wind: and after the wind an earthquake; but the Lord was not in the earthquake: And after the earthquake a fire; but the Lord was not in the fire: and after the fire a still small voice.” The Lord was “in” that “still small voice.”

The account of the destructions in 3 Nephi 8-11 tells of a great “storm,” “tempest,” “thunder” and “whirlwinds,” of fire and an earthquake that broke the rocks, ultimately followed by a “small voice” heralding the Savior’s appearance. Such literary crafting suggests that its author wanted us to think, while reading it, of the story of Elijah.