The American Conquistador

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, July 17, 2020

Hard as it may be to believe today, Americans once believed in Manifest Destiny. The term was coined in 1845 by John L. O’Sullivan, the founder and editor of the United States Democratic Review in New York, and it envisioned a United States that connected the Pacific and the Atlantic. As one historian notes, Manifest Destiny also meant the belief that “white Anglo-Saxons . . . were preordained to spread civilization across the vast continent for the sake of its cultural and economic advancement” [1]. Manifest Destiny was, in a sense, a Yankee version of Venezuelan revolutionary Simon Bolivar’s pan-Americanism.

Perhaps no figure better embodied the spirit of Manifest Destiny than William Walker. Barely remembered in the United States, Walker is reviled in Central America. The Sandinistas of Nicaragua taught children that Walker was the first Yankee “imperialist.” [2]. A film about Walker was released in 1987. Directed by British leftist Alex Cox, Walker is a send-up of Washington’s involvement at that time in the civil war in Nicaragua and elsewhere in Latin America. Cox turned Walker into an early Rambo or a more venomous, less satirical Mr. Freedom. This is the general view of Walker: a bogeyman and pirate determined to turn Latin America into US protectorates.

Indeed, with a private army called the American Phalanx, Walker’s dream was to create an independent republic uniting Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador [3]. The Walker story is complex, full of heroics and betrayals, and left a legacy that continues to the present.

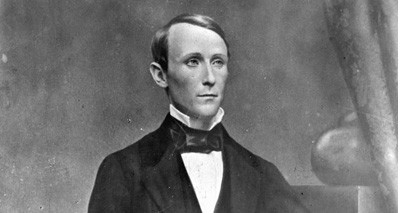

Born on May 8, 1824, the first of six children of Scottish immigrant James S. Walker and his Kentucky-born bride, William Walker grew up in the frontier city of Nashville, Tennessee. Walker’s father made a fortune in steamboats [4], and other members of the family were distinguished: maternal grandfather Lipscomb Norvell was a veteran of the Continental Army, who fought at Trenton and Monmouth. Several of William’s uncles and cousins fought the British during the War of 1812 or the Mexicans during the Texas Revolution. The Walkers were a proud, illustrious family.

William Walker was intelligent and studied hard. He enrolled at the University of Nashville at age 13. There he studied Greek, Latin, trigonometry, international law, and medicine. He graduated summa cum laude in October 1838 at the astonishing age of 14. He then attended the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied medicine. After getting his degree in 1843, Walker traveled in Europe on a generous allowance from his family. He spent nearly two years in Paris, which helped him to understand what he saw as the superiority of American liberty over the “popish” tendencies of the French [5].

Back in the United States, Walker studied law and practiced in New Orleans, but was not successful as a lawyer. By 1849, he had taken a share in the Daily Crescent newspaper where, as editor, he took a moderate stance on slavery.

It is not known when Walker decided on military adventurism, but “filibustering,” or mercenary work, was popular and already had a tradition. In 1819, James Long of Tennessee, after serving in the US Army during the War of 1812, took volunteers from Natchez, Mississippi, and tried to conquer Mexican Texas. The Long Expedition failed.

American Progress (1872) by John Gast.

While Walker was living in New Orleans, Cuban revolutionary Narciso López used American filibusters in several botched attempts to take Cuba from Spain. He wanted Cuba annexed by the United States, preferably as a slave-owning state but was executed by the Spanish authorities. Lopez had admirers in both the American North and South [6].

Walker yearned for adventure. Before the age of 30 and without military training of any kind, he tried to conquer the Mexican state of Sonora. In 1853, he set off for Baja, California, from San Francisco with 100 men. They told the US government they would work in the mines of Sonora, but they carried weapons instead of pickaxes. At the time, Northern Mexico was a desolate place, where roving Apache bands terrorized villagers and wealthy ranchers alike. The corrupt central government in Mexico City could not do much except offer generous settlement grants to foreigners, especially German and French settlers, whom it considered more trustworthy than land-hungry Yankees. Walker considered his adventure a civilizing mission to protect Mexicans from Apache raids.

Walker’s small band took the city of La Paz without much of a fight. From there, the First Independent Battalion, as Walker called his army, established the independent Republic of Lower California. In November 1853, he renamed it — all of Sonora and the Baja Peninsula — the Republic of Sonora, took office as president, and instituted the Civil Code of Louisiana. This meant legalizing slavery, though it remained illegal in the rest of Mexico [7].

The Republic of Sonora’s Flag

The Republic of Sonora lasted until May 1854. Walker’s army of untrained volunteers did more looting than fighting, with an occasional skirmish with local Mexican militia, Indians, and professional Mexican soldiers. Walker’s most powerful enemy may have been President Franklin Pierce’s administration, which saw Walker’s actions as at best a nuisance and at worst a violation of America’s Neutrality Act of 1794. The Republic of Sonora fell to a combination of Mexican military resistance and political pressure by General John E. Wool, the head of US forces on the Pacific coast [8]. Walker and his men retreated to California, where he was put on trial for violating the Neutrality Act, but filibustering was popular and a jury acquitted him in eight minutes.

American industrialists had their eye on both Panama and Nicaragua as potential canal sites to link the Atlantic and Pacific. Even without a canal, American companies such as the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and the Accessory Transit Company were moving men and supplies across Nicaragua to avoid the voyage around Cape Horn. As a result, Nicaragua’s port cities and trading posts had sizable American communities. The largest number of Americans lived in Greytown on the Atlantic coast, which belonged to the Mosquito Kingdom, a protectorate of the British Empire ruled by English-speaking Indians.

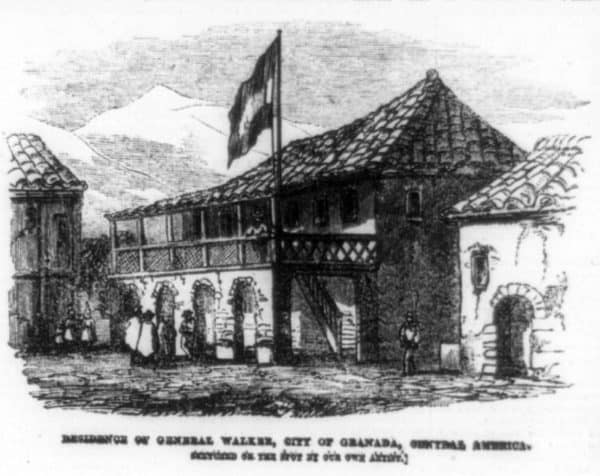

William Walker’s home in Granada, Nicaragua.

The biggest problem with doing business in Nicaragua was the country’s constant civil wars. Ever since independence from Spain, Nicaragua had been fought over by the Legitimist conservatives based in Granada and the Liberals headquartered in León. As much a familial and municipal feud as a political one, civil wars lasted well into the 20th century and required several US military interventions [9]. Thanks to an election in 1853 that did not produce a majority, Nicaragua fell into civil war again.

From a sanctuary in Honduras, the Liberals under Francisco Castellón sought foreign volunteers for their army. Many Americans, including Walker, answered the call. Walker and two San Franciscans approached Castellón and reached an agreement whereby they would get 21,000 acres of land and military wages if they would recruit and command an army of 300 men against the Legitimists in Granada [10]. Walker took command of this force, the American Phalanx, that immediately went into action with just 150 men at the First Battle of Rivas. The Legitimist defenders repulsed an initially successful American charge, and killed several of Walker’s officers during repeated attempts to overrun barricades.

The Phalanx moved back to the Pacific coast where it commandeered several ships. Walker recognized that controlling the river routes to the ocean was vital not only because he could pillage the supply depots of the Accessory Transit Company (demonstrating that Walker was hardly an agent of American capital as Leftists like to argue), but he could also safely bring in new volunteers from the United States. According to his own records, from January to April 1857, Walker’s Phalanx had 1,072 soldiers and 250 officers. Walker has often been called the vanguard of Southern expansionism, but most of his men came from non-slave-holding regions [11].

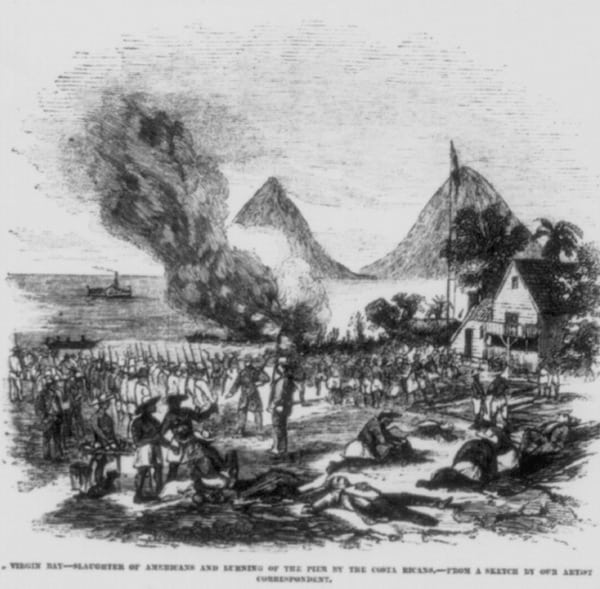

Walker had a few professional mercenaries and veterans of the Mexican-American War, but most of his men had no military experience and brought their own weapons and food. Many deserted, and cholera ravaged not only the Phalanx but all the armies in the field. Still, 150 Phalanx soldiers cut a larger Legitimist force to ribbons with superior rifles and won the Battle of Virgin Bay. Walker then captured Granada by using commercial ships as gunships. He threatened to level the town and kill Legitimist families unless the conservatives agreed to form a provisional government that included both Legitimists and Liberals.

The financially exhausted provisional government that emerged could not stop Walker from taking over the country. Both the Legitimists and Liberals relied on conscripts, so when walker ended conscription, the Phalanx was the only remaining military force. Walker called for a general election but the Legitimists and the Liberals — both now disenchanted with Walker — boycotted it. This ensured victory for Walker, who proclaimed himself president of Nicaragua.

The Nicaraguan Flag During the Reign of William Walker

This united Nicaragua’s neighbors against Walker. Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Costa Rica joined forces with the remnants of Nicaragua’s two armies to expel Walker’s 850 men. They opposed Walker along racial lines, saying that he wanted to replace the mestizo nations of Central America with whites [12]. Walker did have a racial vision. He argued that his army, which represented naturalized citizens of Nicaragua, had the right to rule, not only because they had shed their blood, but because generations of corruption required Anglo-Saxons to set things right. The war to remove President Walker became a war of extermination, as the Costa Rican army executed American and European merchants and farmers [13].

Cornelius Vanderbilt entered the fray as the most powerful member of the anti-Walker coalition. Opposed to filibustering and incensed at Walker’s expropriation of Accessory Transit Company property, Vanderbilt hired a New York ruffian and former murder suspect named Sylvanus Spencer to retake the ships Walker had taken over. Spencer did his job well, and his crew of 120 Costa Rican soldiers successfully destroyed Walker’s navy while the Phalanx fought for its life against thousands of Central American soldiers. Without an ocean escape route, Walker’s men were forced to abandon Granada after a grueling siege [14].

An illustration of one of William Walker’s Central American battles in 1856.

Fighting, retreats, disease, and desertion decimated Walker’s army. On May 1, 1857, Walker and his remnant of soldiers, POWs, and Nicaraguan loyalists surrendered to Captain Charles H. Davis of the US Navy. The undaunted Walker returned to New Orleans still proclaiming himself as the legitimate president of Nicaragua.

After a lecture tour through New Orleans, San Francisco, and New York, Walker was approached by a representative of the Bay Islands. Located off the coast of Honduras, the islands belonged to the British Empire as part of its Mosquito Kingdom protectorate. However, in 1860, London signaled to Honduras that it wanted to give up the islands if the Honduran government would agree to respect the rights of British citizens living there. London encouraged the islanders to relocate to Jamaica or Barbados, but a delegate asked Walker to assemble a new force to defend the islands against Honduras. Walker agreed.

In June 1860, Walker’s expedition set off from Cozumel, Mexico, and planned to land at Coxen Hole on the Bay Islands (now the island of Roatán). Patrolling Royal Navy ships convinced Walker to land at Trujillo on the Honduran mainland instead. There, Walker’s men took the town of Fortaleza de Santa Bárbara with minor losses, but the victory was pyrrhic. Commander Nowell Salmon of the Royal Navy threatened to unleash his guns on the Americans. Walker agreed to surrender to Salmon as a representative of the British crown, but Salmon deceived him. Since Walker continued to claim to be president of Nicaragua, Commander Salmon forced Walker into Honduran custody on charges of an unlawful declaration of war against a peaceful neighbor. A Honduran firing squad executed the 36-year-old William Walker on September 12, 1860.

William Walker homesite in Nashville, Tennessee. (Image via LatinAmericanStudies.org)

Those who wrote about Walker agreed that his dream was to build an English-speaking empire in Central America. As dictator, Walker would establish an independent republic that would offer a regional alternative to both the US and the British Empire.

Walker had several reasons for supporting slavery. He understood that a slave-owning republic could more easily trade with the South and attract Southern immigrants. He also believed in the superiority of Anglo-Saxon civilization, saying that the “half caste” majority of Nicaragua as well as Africans enjoyed the “teaching of the arts of life” thanks only to Europeans [15]. Nevertheless, Walker believed he had become a citizen of Nicaragua and that his government had improved life for the people. Walker even converted to Catholicism to show his commitment to his adopted country.

After the Civil War, thousands of Southerners tried to follow Walker’s lead by moving to Latin America to escape Northern tyranny. Confederate veterans established colonies such as New Virginia in Mexico and Americana in Brazil. The latter, which saw 10,000 Southern immigrants establish Protestant churches and modern farms in the Brazilian jungle, still celebrates Confederate history and heritage. Frank McMullen, a Texan who fought in the Phalanx in Nicaragua, was the leader of the Southern presence in Brazil. Some 5,000 Southerners, many of them Confederate veterans such as General John B. Magruder, pledged loyalty to Emperor Maximilian of Mexico and fought for his empire.

All of these men were imbued with the spirit of William Walker — the closest thing America ever had to a conquistador. And perhaps Walker’s dream isn’t dead. As recently as 2018, a few Bay Islanders asked to return to the British Commonwealth, rather than remain as part of Honduras. Perhaps, someday, a man will come with the courage to carve out a private kingdom.

* * *

[1]: Scott Martelle, William Walker’s Wars: How One Man’s Private American Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2019): 20.

[2]: Stephen Kinzer, “Nicaragua: The Beleaguered Revolution,” New York Times Magazine, 28 Aug. 1983, <https://www.nytimes.com/1983/08/28/magazine/nicaragua-the-beleaguered-revolution.html>.

[3]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 201.

[4]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 9.

[5]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 17.

[6]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 34.

[7]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 67.

[8]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 86.

[9]: Benjamin Welton, “Uncle Sam’s Intervention,” Military History, January 2020.

[10]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 119.

[11]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 203.

[12]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 185.

[13]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 186.

[14]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 209-210.

[15]: Martelle, William Walker’s Wars, 200.

[16]: An Authentic Exposition of the “K.G.C.” or, A History of Secession from 1834 to 1861 (Indianapolis: C.O. Perrine): 186