(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

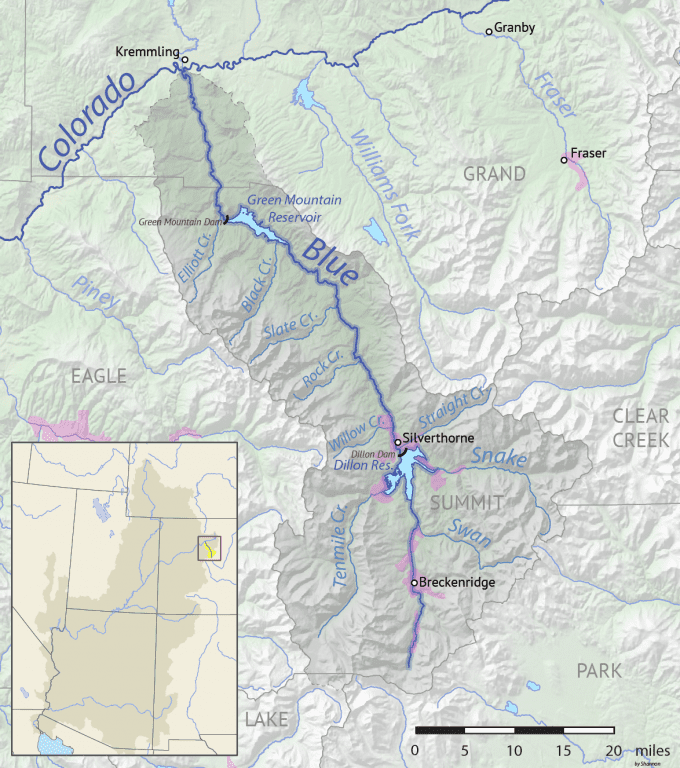

When we were out and about along the Blue River near Breckenridge, Colorado, the other day, this passage in Felicie Williams and Halka Chronic, Roadside Geology of Colorado, 3rd ed. (Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2014) struck me:

Glaciers flowing down this valley and its side canyons scoured the mountain walls, exposing and grinding up gold-bearing veins. Swift mountain streams, able to transport heavy loads, carried the glacial debris downhill, rounding its boulders and cobbles, sorting it by size, and dropping it, gold and all, where they slowed down in the gentler valley below. Nineteenth-century prospectors discovered these stream-formed placer deposits and with simple tools like shovels, goldpans, rockers, and sluices recovered what gold they could from near the top of the deposits.

But gold is six times as heavy as most rocks and tends to settle in deeper parts of stream deposits. Near Breckenridge the valley has been worked over by a large gold dredge able to scoop up deep coarse gravel mechanically and to separate the gold from it right on the dredge, leaving the left-over gravel tailings in bouldery ridges. (214)

I was instantly reminded of such passages as these, which I’ve quoted here before:

I sent my boy to harness my horse and take her [Lucy Mack Smith, Joseph’s mother] home. She wished my wife and daughter to go with her; and they went and spent most of the day.

When they came home, I questioned them about them [the plates]. My daughter said, they were about as much as she could lift. They were now in the glass-box, and my wife said they were very heavy. They both lifted them. . . .

While at Mr. Smith’s I hefted the plates, and I knew from the heft that they were lead or gold; and I knew that Joseph had not credit enough to buy so much lead. (Martin Harris, cited by Hyrum L. Andrus and Helen Mae Andrus, Personal Glimpses of the Prophet Joseph Smith [American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2009], 34, 35)

They were not quite as large as this Bible. Could tell whether they were round or square. Could raise the leaves this way (raising a few leaves of the Bible before him). One could easily tell that they were not stone, hewn out to deceive, or even a block of wood. Being a mixture of gold and copper, they were much heavier than stone, and very much heavier than wood. (“The Old Soldier’s Testimony,” a sermon preached by William B. Smith in the Saints’ Chapel at Deloit, Iowa, on 8 June 1884, and reported by C. E. Butterworth, in The Saint’s Herald 31 [1884]: 644)

Along those lines, I append a comment from Pamela B. Zohar, made in connection with a completely non-LDS-related entry at Quora:

Pure gold has a specific gravity of 19.32, meaning it masses 19.32 times what a same-sized amount of water would mass.

The average rock masses around 2.6 times that of water.

So gold — compared to the average rock or mineral — is about 7.4 times heavier (more massive) than a rock of the same size. You would definitely notice the difference.

Gold is . . . extremely heavy, with a density of 19.4 g cm-3. The density of lead, by comparison, is only 11.4 g cm-3.

Most of us today have little personal experience with “hefting” large quantities of lead and gold, so I thought that the references might be helpful.