A Startlingly Sensible Government Report

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, March 12, 2021

Thumbnail credit: Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Alpha Stock Images

An unpublicized report from the Department of Commerce states that online free speech does not lead to more hate crimes. It also says that the concept of “hate speech” is essentially meaningless and that even “hate crime” legislation rests on shaky legal grounds. It argues that censoring “hate speech” does no good and that social media companies should stop doing it. It’s not surprising the Biden Administration appears to have concealed this report (available here).

This updates a 1993 report called “The Role of Telecommunications in Hate Crimes,” which is available online. We know about the 2020 version only because Allum Bokhari of Breitbart got a copy. He quotes an unnamed source, who says that the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice opposed releasing the report because the bureaucracy is trying to “drum up hysteria” over alleged white nationalist extremism.

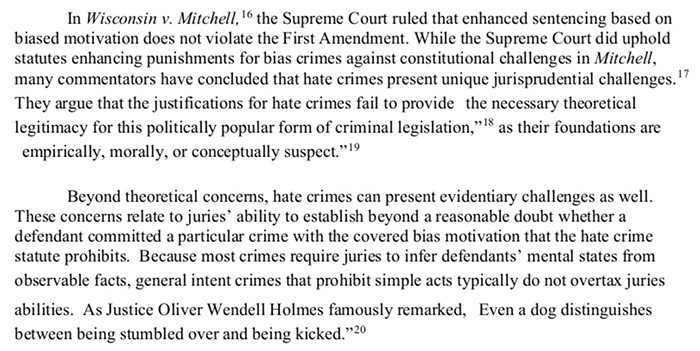

The report questions the legitimacy of the very idea of hate crimes. After describing “hate crimes” legislation in various states and localities, it says “many commentators” think the very concept is murky. Page seven of the report (the report is not available as text, only as an image):

Footnote 16 to Wisconsin v. Mitchell cites an important article, “What if Wisconsin v. Mitchell Had Involved Martin Luther King Jr.? The Constitutional Flaws of Hate Crime Enhancement Statutes” by Steven Gey, which questions the legitimacy of hate crimes legislation. The unnamed author of the Commerce report added a brief excerpt suggesting that “the Court blinked” in upholding the hate crime statue in what was a departure from the Court’s good record of using “liberal principles on behalf of an illiberal and reviled defendant.”

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Wisconsin v. Mitchell that the “hate” criminal should do more time, and that this did not punish bigoted beliefs or statement. The theory is that extra punishment deters the ramifications of bigotry. “Hate crime” legislation is constitutional because it does not criminalize speech or thought.

Credit Image: © Creative Touch Imaging Ltd/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press

This report counters what many journalists and politicians argue today. They tell us government must restrict free speech and deplatform racists because whites are being “radicalized” to commit hate crimes. Many of President Donald Trump’s critics said he was demonizing minorities and thus provoking someone to violence, even if we don’t know in advance who that might be. I’m sure that many people think American Renaissance should be shut down because we “radicalize” whites who commit crime.

I would argue that since leftists control most media and use violent rhetoric, they are guilty of creating an environment that promotes violence. Politicians, universities, and media demonize “whiteness” or (when they are clumsy) whites, which surely leads to crimes against whites. Blacks are much more likely to commit crimes against whites than whites against blacks. Is it farfetched to say those with power incite at least some of those crimes?

That’s what happened in Wisconsin v. Mitchell. On October 7, 1989, a group of young blacks were talking about the movie Mississippi Burning, which demonizes whites who resisted desegregation. Todd Mitchell asked, “You all want to f**k somebody up? There goes a white boy; go get him.” Mr. Mitchell egged on the attack but didn’t participate, while his friends beat a young white boy into a coma. Mr. Mitchell was convicted of aggravated battery in Kenosha County, Wisconsin, which is where Kyle Rittenhouse had a deadly confrontation with antifa more than two decades later.

The trial court increased Mr. Mitchell’s sentence because of the racial motivation, but the Wisconsin Supreme Court threw out the extra punishment on First Amendment grounds. The Supreme Court then reversed. If the Court had found hate crime legislation unconstitutional, the legal landscape would be very different. There would be no Hate Crimes Unit at the Department of Justice, no constant demands to track “hate crimes,” and journalists would lack an important rationale for deplatforming white advocates. Ironically, the Supreme Court’s ruling on the legitimacy of hate crime laws involved a racially motivated attack on a white man.

Steven Gey’s article criticizes the decision, arguing that the Supreme Court gave “short shrift to the First Amendment considerations” cited by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Mr. Gey notes that the “popular press” praised the decision, but he says the Court dodged important, complicated issues.

The famous 1969 case of Brandenburg v. Ohio found that even speech that arguably incites violence is protected unless it can reasonably be thought to incite imminent, lawless action. In this case, a Ku Klux Klan leader vaguely referred to violence against political enemies. The Court struck down the law used against him because there was no direct imminent threat equivalent to saying something, “There goes a black boy; go get him.”

Mr. Gey suggests that the Wisconsin case was both simpler and more complicated than Brandenburg. It was simpler because it was clear incitement to direct violence — even if Mr. Mitchell did not take part. But what justified a longer prison term? The fact that the victim was of a different race and because the crime presumably caused more harm to society than a non-racist assault? Mr. Gey is right to suggest that these questions become “surprisingly deep,” not least because judges and juries must be able to read the minds of defendants.

The Supreme Court did underline the difference between constitutionally protected “hate speech” and actual crime, but the unpublicized report notes that the distinction is murky:

Therefore, so-called “hate speech,” a term that has no consistent or well-accepted definition, cannot constitute advocacy or encouragement of hate crimes without explicitly calling for particular acts to be performed with specific motivations. Rather, to advocate for or encourage hate crimes requires advocacy of particular criminal acts as well as advocacy or encouragement that the criminal act of each of such crimes have a particular motivation.

Mr. Gey criticizes Mitchell because it implies that the defendant’s racial comment was inseparable from the attack or caused greater social harm. It’s not clear that was the case, and here is Mr. Gey’s key conclusion:

Mitchell’s enhanced penalty cannot be upheld unless the Court is willing to countenance punishing racism because racism itself, in all its manifestations, threatens the public order so greatly that its expositors must be punished for their views as well as their actions. (p. 1033-1034)

If that’s the case, there are legal grounds to police speech:

The state seeks to prevent aggravated battery without regard for either the purpose of the act or the identity of the perpetrator. The state seeks to punish racial hatred, on the other hand, because it has deemed the ideas themselves, and those who possess them, politically dangerous. (p.1035)

People may sincerely believe “racism” should be a crime, but Mr. Gey notes that this would require that the Supreme Court be “willing to reconsider some of the most basic principles of First Amendment free speech jurisprudence.” Was what Mr. Mitchell said truly a crime? What if he had just been talking big and had no idea his friends would act on what he said? If he had made the same anti-white remark, but there were no white people to attack — and there had been no violence — would he still have committed a crime?

Mr. Gey argues that the Court essentially held that certain thoughts when expressed cause violence and should therefore be punished. This means that “the basic problem with Mitchell is that it permits the government to use its authority to punish criminal action as a cloak to punish political dissent.” (p. 1067)

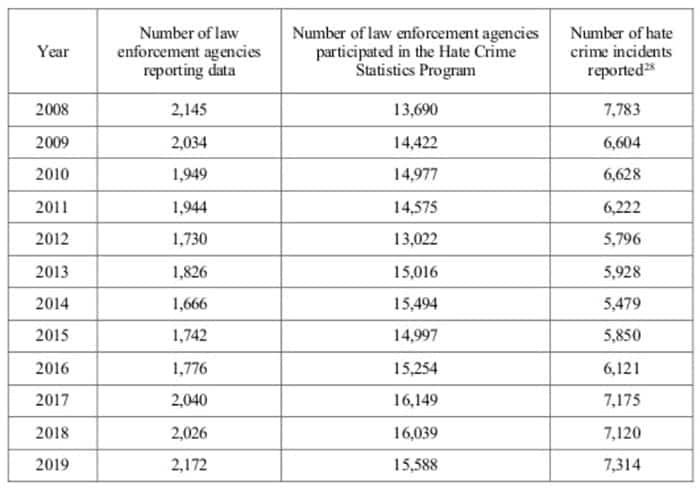

Even if the author of this Department of Commerce report thinks “hate crime” legislation is illegitimate, we are stuck with it. The report analyzes the number of hate crimes reported through the Justice Department’s Uniform Crime Reporting System and the National Crime Victimization Survey and finds that “the evidence does not show that during the last decade, a time of explosive growth of electronic communications, particularly on the Internet and mobile devices as well as social media, there has been a rise in hate crime incidents.” (p. 10)

The author recognizes that people who commit hate crimes use the Internet, but research shows no “causal relationship between increased social media use and violence.” There are no data that correlate increased hate speech on social media with increased hate crimes and, in any case, it may be impossible to define “hate speech:”

The confusion about the meaning of hate speech is revealed by even the most cursory review of the social media platforms policies and practices. While most platforms utilize community guidelines that strictly prohibit hate speech, researchers have noted persistent inconsistencies relating to the intractable problem in defining hate speech.

The report notes that social media censorship probably achieves nothing, even by the companies’ own standards:

Given that all the major social media platforms have rules against hate speech and, in fact, employ sophisticated algorithmic artificial intelligence (AI) approaches to enforce these often vague and contradictory rules in a manner also used by tyrannous regimes, it is appropriate to ask what they gain from it. Certainly, as this Report shows, the platforms have no reasonable expectation that their censorship will end hate crimes or even diminish it, as no empirical evidence exists linking increased hate speech with hate crimes.

The report even notes — remarkable given today’s climate — that social media companies have “removed content that many consider seriously engaged with pressing political and social issues.” (p. 14) It goes on to make the case that social media companies are now public fora and could be reasonably held to First Amendment free-speech standards. This is the same argument American Renaissance made in its ultimately unsuccessful suit against Twitter in 2018. From the Commerce report:

Government regulation of a private entity may transform that private entity into a state actor or public forum subject to the First Amendment.

Ordinarily, the First Amendment does not apply to private actors. However, the state- action doctrine provides that a private entity can be held to the standard of a state actor when the private entity exercises a function traditionally exclusively reserved to the state.” In Manhattan Community Access Corporation v. Halleck, the Supreme Court determined that a private entity’s operation of public access channels on a cable system did not transform the entity into a state actor, and therefore, was not subject to the constraints of the First Amendment, despite New York State’s extensive regulation of the entity.

On the other hand, courts have also ruled that social media can be considered public forum subject to the First Amendment. Knight First Amendment Inst. at Columbia Univ. v. Trump ruled that President Trump’s Twitter account was a public forum to which the First Amendment applies. The court ruled that the President and Scavino [the White House social media director] exert governmental control over certain aspects of the @realDonaldTrump account, including the interactive space of the tweets sent from the account. That interactive space is susceptible to analysis under the Supreme Court s forum doctrines, and is properly characterized as a designated public forum.” Similarly, Robinson v. Hunt County involved a governmental social media account, in particular, a sheriff office’s Facebook page. The court ruled that public fora First Amendment rules applied.

Credit Image: © Christoph Hardt/Action Press via ZUMA Press

This thinking would lead to an end to deplatforming for political reasons.

The report offers no protection against other kinds of deplatforming, however. “Private banking and financial firms, are, of course, free, aside from the obligation not to discriminate against certain groups such as women, or racial minorities, to do business with whomever they choose.” Apparently, white male privilege goes only so far. Still, the report reaches a heartening conclusion: There is “no reason to believe that censoring hate speech will make hate crimes less likely.”

During the Trump Administration, media routinely claimed that the President made claims “without evidence.” NPR itself said this had become a catchphrase. The media are, themselves, in the business of making claims “without evidence.” You could almost argue that the role of American Renaissance is to point this out.

At least some people in the government are challenging claims about “hate crimes” that are widely made “without evidence.” If this report were taken seriously, it could lead to a return to real freedom of speech on the internet. No wonder the Biden administration wants no one to read it.