Recompose human composting facility "transforms your loved one's body into soil"

American startup Recompose has opened a funeral home in Seattle designed by architecture firm Olson Kundig, where human remains are composted and turned into a nutrient-rich soil that can nurture new plant life.

Set in a converted warehouse in the city's SoDo district, the facility is one of the first to make use of a burgeoning practice known as natural organic reduction – or human composting, which was legalised in the state of Washington in 2019.

This sees the body of the deceased placed on a bed of plant materials inside a stainless steel vessel, purpose-built to accelerate the natural process of decomposition.

Over the course of 60 days, their remains are converted into one cubic yard of fertile soil – enough to fill the bed of a pickup truck. Loved ones can then take this compost home and use it to nourish their garden, plant trees in memory of the deceased or donate it to a local conservation area.

The aim is to offer a less polluting alternative to cremation or burial, which are hugely emissions and resource intensive, and instead create a meaningful funeral practice that allows people to give back to nature.

"Clients have shared with us that the idea of their person becoming soil is comforting," Recompose founder Katrina Spade told Dezeen.

"Growing new life out of that soil is profound and the small ritual of planting, using soil created from a loved one's body, is so tangible."

Recompose's 19,500-square-foot flagship facility in Seattle accommodates an array of 31 cylindrical composting vessels, stacked inside a hexagonal steel framework.

This vertical construction helps to conserve space in a bid to overcome the land-use issue associated with traditional burial and make human composting feasible even in dense urban areas.

"Recompose can be thought of as the urban equivalent to natural burial – returning us to the earth without requiring lots of land," said Spade, a trained architect who developed the vessels as part of a residency at Olson Kundig's Seattle studio.

The building itself was designed in collaboration with the architecture studio to reimagine the experience of being in a funeral home, making the process more transparent and bringing in elements of nature instead of overt religious iconography.

In the spirit of regeneration, much of the warehouse's original shell was preserved. Warm wooden flooring and a planted wall enliven the central lobby, while strips of green glass are inset into the walls to provide glimpses of the intimate ceremony space beyond.

Here, loved ones can participate in a "laying-in ceremony", similar to a traditional funeral service.

"The Gathering Space has floor-to-ceiling coloured glass windows that let light in, similar to the way light filters between trees in a forest," said Olson Kundig design principal Alan Maskin.

"In a way, Recompose is a funeral home turned inside-out. There's a suggestion of transparency and openness about death – including the ability to see and understand the entire process – that's very different from a traditional funeral home experience."

During the ceremony, a simple wooden lectern allows the bereaved to share words about their loved ones while the body of the deceased is draped in a cotton shroud and presented on a dark green bed called a cradle.

Mimicking the ritual of throwing dirt on a casket, guests can place flowers and plant materials on their person, which will help their transformation into soil.

The funeral home also has dedicated rooms for those who want to perform more hands-on care for their deceased ahead of the ceremony by bathing the body or reciting prayers and songs.

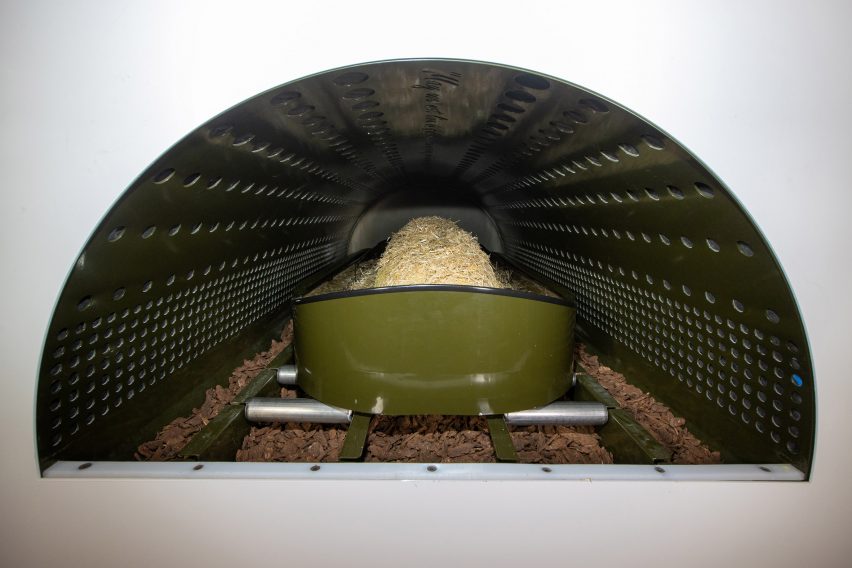

At the end of the service, the cradle is moved through a so-called threshold vessel embedded into the wall and into the Greenhouse, where it will join the other vessels in the array.

"A tremendous amount of care was taken to consider the experience of the body," Maskin said. "There's even a bit of poetry inscribed along the inside of the transitional vessel used during ceremonies."

"That poem isn't for the living; it's only visible inside the vessel."

Each vessel in the array contains a mix of plant materials developed by Recompose that includes wood chips, straw and a cloverlike plant called alfalfa, with ratios adapted based on the person's body and weight.

Over the course of 30 days, the natural microbes found in the plants and the body will break down the remains, with any unpleasant odours filtered out and fresh air – and sometimes moisture – pumped into the vessel, which is intermittently rotated to speed up decomposition.

At the end of this process, any remaining bone fragments are ground down using a cremulator and any medical implants are removed for recycling.

The remaining soil is placed in a curing bin to dry out for another two to six weeks before it can be collected by friends or family.

Unlike cremation, this process does not require huge amounts of energy and fossil fuels, Recompose says, while the carbon contained in the human body is sequestered in the soil rather than released into the atmosphere.

The process also forgoes the vast amounts of embalming chemicals and emissions-intensive materials like steel and concrete that are needed for burials.

In total, the process to "transform your loved one's body into soil" saves around one metric ton of CO2 emissions per person compared to burial or cremation, Recompose claims.

Since 2019, a number of US states have followed in Washington's footsteps and legalised natural organic reduction, with New York joining Colorado, Oregon, Vermont and California last month.

This comes as people are increasingly becoming aware of the hidden environmental impact of the deathcare industry and moving towards alternative funeral practices from liquid cremation to burial pods that grow into trees.

"Members of the baby boomer generation have started experiencing the deaths of their parents and I think many are asking: was that the best we can do," Spade said.

"But what's interesting is that it's not only older folks," she added.

"Over 25 per cent of our Precompose [prepayment plan] members are under 49. I think this is because the climate crisis has played a role, too. People are wondering why our funeral practices haven't been considered when it comes to our carbon footprint."

Recompose plans to expand into Colorado in 2023 and California in 2027, while rival company Earth Funeral has set its sights on Oregon.

The photography is by Mat Hayward/Getty Images for Recompose unless otherwise stated.