Abstract

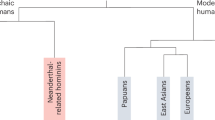

Human evolutionary history is rich with the interbreeding of divergent populations. Most humans outside of Africa trace about 2% of their genomes to admixture from Neanderthals, which occurred 50–60 thousand years ago1. Here we examine the effect of this event using 14.4 million putative archaic chromosome fragments that were detected in fully phased whole-genome sequences from 27,566 Icelanders, corresponding to a range of 56,388–112,709 unique archaic fragments that cover 38.0–48.2% of the callable genome. On the basis of the similarity with known archaic genomes, we assign 84.5% of fragments to an Altai or Vindija Neanderthal origin and 3.3% to Denisovan origin; 12.2% of fragments are of unknown origin. We find that Icelanders have more Denisovan-like fragments than expected through incomplete lineage sorting. This is best explained by Denisovan gene flow, either into ancestors of the introgressing Neanderthals or directly into humans. A within-individual, paired comparison of archaic fragments with syntenic non-archaic fragments revealed that, although the overall rate of mutation was similar in humans and Neanderthals during the 500 thousand years that their lineages were separate, there were differences in the relative frequencies of mutation types—perhaps due to different generation intervals for males and females. Finally, we assessed 271 phenotypes, report 5 associations driven by variants in archaic fragments and show that the majority of previously reported associations are better explained by non-archaic variants.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All summary statistics such as archaic fragments and which SNPs they contain are available as Supplementary Data. Because Icelandic law and the regulations of the Icelandic Data Protection Authority prohibit the release of individual level and personally identifying data, collaborators who want access to individual genotype level data have to access the data locally at our Icelandic facilities.

Code availability

The Python script for performing simulations is available on Github (https://github.com/LauritsSkov/ArchaicSimulations).

References

Prüfer, K. et al. A high-coverage Neandertal genome from Vindija Cave in Croatia. Science 358, 655–658 (2017).

Fu, Q. et al. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514, 445–449 (2014).

Browning, S. R., Browning, B. L., Zhou, Y., Tucci, S. & Akey, J. M. Analysis of human sequence data reveals two pulses of archaic Denisovan admixture. Cell 173, 53–61 (2018).

Wall, J. D. et al. Higher levels of Neanderthal ancestry in East Asians than in Europeans. Genetics 194, 199–209 (2013).

Kim, B. Y. & Lohmueller, K. E. Selection and reduced population size cannot explain higher amounts of Neandertal ancestry in East Asian than in European human populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 454–461 (2015).

Vernot, B. & Akey, J. M. Complex history of admixture between modern humans and Neandertals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 448–453 (2015).

Villanea, F. A. & Schraiber, J. G. Multiple episodes of interbreeding between Neanderthal and modern humans. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 39–44 (2019).

Dannemann, M. & Kelso, J. The contribution of Neanderthals to phenotypic variation in modern humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 578–589 (2017).

Gittelman, R. M. et al. Archaic hominin admixture facilitated adaptation to out-of-Africa environments. Curr. Biol. 26, 3375–3382 (2016).

Gregory, M. D. et al. Neanderthal-derived genetic variation shapes modern human cranium and brain. Sci. Rep. 7, 6308 (2017).

McCoy, R. C., Wakefield, J. & Akey, J. M. Impacts of Neanderthal-introgressed sequences on the landscape of human gene expression. Cell 168, 916–927 (2017).

Dannemann, M., Prüfer, K. & Kelso, J. Functional implications of Neandertal introgression in modern humans. Genome Biol. 18, 61 (2017).

Simonti, C. N. et al. The phenotypic legacy of admixture between modern humans and Neandertals. Science 351, 737–741 (2016).

Vernot, B. & Akey, J. M. Resurrecting surviving Neandertal lineages from modern human genomes. Science 343, 1017–1021 (2014).

Sankararaman, S. et al. The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature 507, 354–357 (2014).

Steinrücken, M., Spence, J. P., Kamm, J. A., Wieczorek, E. & Song, Y. S. Model-based detection and analysis of introgressed Neanderthal ancestry in modern humans. Mol. Ecol. 27, 3873–3888 (2018).

Meyer, M. et al. A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science 338, 222–226 (2012).

Prüfer, K. et al. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature 505, 43–49 (2014).

Slon, V. et al. The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature 561, 113–116 (2018).

Skov, L. et al. Detecting archaic introgression using an unadmixed outgroup. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007641 (2018).

Kong, A. et al. Detection of sharing by descent, long-range phasing and haplotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 40, 1068–1075 (2008).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Sankararaman, S., Mallick, S., Patterson, N. & Reich, D. The combined landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Curr. Biol. 26, 1241–1247 (2016).

Vernot, B. et al. Excavating Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from the genomes of Melanesian individuals. Science 352, 235–239 (2016).

Schumer, M. et al. Natural selection interacts with recombination to shape the evolution of hybrid genomes. Science 360, 656–660 (2018).

Harris, K. & Pritchard, J. K. Rapid evolution of the human mutation spectrum. eLife 6, e24284 (2017).

Moorjani, P., Amorim, C. E. G., Arndt, P. F. & Przeworski, M. Variation in the molecular clock of primates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10607–10612 (2016).

Jónsson, H. et al. Parental influence on human germline de novo mutations in 1,548 trios from Iceland. Nature 549, 519–522 (2017).

Harris, K. & Nielsen, R. The genetic cost of Neanderthal introgression. Genetics 203, 881–891 (2016).

Juric, I., Aeschbacher, S. & Coop, G. The strength of selection against Neanderthal introgression. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006340 (2016).

Castellano, S. et al. Patterns of coding variation in the complete exomes of three Neandertals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6666–6671 (2014).

McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

Sveinbjornsson, G. et al. Weighting sequence variants based on their annotation increases power of whole-genome association studies. Nat. Genet. 48, 314–317 (2016).

Kote-Jarai, Z. et al. Identification of a novel prostate cancer susceptibility variant in the KLK3 gene transcript. Hum. Genet. 129, 687–694 (2011).

Hajdinjak, M. et al. Reconstructing the genetic history of late Neanderthals. Nature 555, 652–656 (2018).

Besenbacher, S., Hvilsom, C., Marques-Bonet, T., Mailund, T. & Schierup, M. H. Direct estimation of mutations in great apes reconciles phylogenetic dating. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 286–292 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Pruefer, B. Vernot, B. Peter, J. Kelso and S. Pääbo for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. The study was supported by grant NNF18OC0031004 from the Novo Nordisk Foundation and grant 6108-00385 from the Research Council of Independent Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S., M.C.M. and G.S. analysed the data with input from H.J., B.H., D.F.G., A.H. and M.H.S. L.S. and M.C.M. created the methods for analysing the data. L.S., M.C.M., A.H., F.M., K.S. and M.H.S. designed the study. L.S., M.C.M., A.H. and M.H.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All of the authors (except for L.S., M.C.M., F.M., E.A.L. and M.H.S.) are employees of deCODE Genetics and Amgen.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Stephan Schiffels and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Estimates of the false-positive rate of archaic inference based on simulations.

a, Length distributions of false-positive and true-positive calls for fragments inferred to be archaic, and the length distributions for simulated archaic fragments that were found and those that were missed. The dashed lines indicate the mean value of the distribution. b, False-positive rate as a function of the mean posterior probability of being archaic for each fragment.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Properties of SNP classes in archaic fragments.

a, The site frequency spectrum for DAV variants, DAV-linked variants, DAV-unlinked variants and non-DAV variants. The x axis shows variants found on 1–250 chromosomes in our Icelandic population sample and the y axis shows the number of variants in each category. b, The number of times a variant is found in European populations (Utah residents (CEPH) with northern and western European ancestry (CEU), Toscani in Italy (TSI), Finnish in Finland (FIN), British in England and Scotland (GBR) and Iberian population in Spain (IBS); codes as per the previous study) from the 1000 Genomes Project (1000G) as a function of the number of times it is observed in Iceland. The numerical labels represent the number of variants that belong to each category defined by the two axes and the type of archaic variant. The x axis is truncated at variants that were found 2,500 times, which corresponds to a frequency of around 5% in Iceland.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Nucleotide diversity based on DAV-linked and DAV variants from archaic fragments.

Using these variants, we identified a maximum of 6 subgroups of fragments, clustered by similarity (based on a mean difference of 1 mismatch per 10 kb per subgroup).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Length distribution and coalescence time for all archaic fragments.

The distribution of length and coalescence times (with present day sub-Saharan Africans) for all archaic fragments (mosaic and non-mosaic) are shown according to the archaic genome that they are most closely related to (Altai, Denisova, Vindija, multiple archaics (ambiguous) and unknown). The coalescence time estimates are described in Supplementary Information 2.7.

Extended Data Fig. 5 A genomic map of archaic introgression deserts.

a, The mean frequency of archaic fragments in each 100-kb bin is reported along the genome (ideogram). The y axis is truncated at 5%. Regions with no archaic fragments (only counting fragments with DAV variants and DAV-linked variants) in regions larger than 1 Mb (and a minimum of 100 kb could be called) are marked in green, along with previously reported deserts in red23 and blue24. b, The size distribution of archaic introgression deserts. c, Gene density in deserts (n = 570) compared with non-deserts (n = 2,224). The numbers indicate the mean number of genes per Mb and the error bars are 95% confidence intervals. The y axis is truncated at 25 genes per Mb.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Archaic introgression and genomic features in 250-kb windows for which more than 1% of the bases in the window could be called.

n = 10,466. a, b, The relationship between the nucleotide diversity of archaic fragments (a) or their frequency (%) (b) and the recombination rate (cM per Mb) and gene density (number of genes per 250 kb). Data were analysed by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and P values for all data points (two-sided test) are shown. For visualization, we group the data into five equally sized bines, sorted by diversity (a) or frequency (b). Each bin contains 2,093 data points. In this analysis, we considered only DAV-linked variants and DAV variants. The data are coloured according to which feature is being tested (blue for frequency, orange for genes, green for recombination rate and yellow for diversity). The midpoint of the bar is the mean of the measure and error bars are 95% confidence intervals. The y axis is truncated at five times the mean value.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Difference between observed and simulated fragments based on increasing Neanderthal-to-human mutation rates.

a, The square-root difference of the 10-replicate mean simulated scenarios for ∆AH (difference scenarios have mutation rates of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4%) and the observed values of ∆AH for the Icelandic fragments, after trimming different numbers of 5-kb bins from the ends of each fragment. The analysis was repeated applying 0-, 50-, 100-, 150- and 200-kb minimum fragment length filters (facets). b, As in a, but adding up the square-root difference value for all the bins trimmed and ranking each bar by the minimum difference (number on top of each bar: 1, minimum difference; 5, maximum difference).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains the consortium authorship and acknowledgements.

Supplementary dataset 1

This dataset consists of mosaic and nonmosaic fragments that have an average posterior probability above 0.9. All analysis regarding fragment length distribution, variant density and relation to the sequenced archaic individuals use these fragments. The coordinates are given in human reference genome build hg38.

Supplementary dataset 2

This dataset constists of all SNPs that are classified as archaic i.e. being with the fragments described in SIdataset1.txt. For each SNP the position are given in human reference genome build hg38. For each SNP we provide information about how often the SNP was found on the archaic background vs the human background and which archaic reference genomes the SNP was shared with.

Supplementary dataset 3

In the first tab of the excel spreadsheet is SI Table 2.6.1 from section 2. In the tab called “Neanderthal demography fitting” is the same summary of 250 simulations varying parameters related to the Neanderthal population as described in SI Figure 3.1.1. In the tab called “Denisova demography fitting” is the same summary of 576 simulations varying parameters related to the Denisovan admixture as described in SI Figure 3.1.1.

Supplementary dataset 4

This dataset reports the chrom, desert number, start, mean windows called as archaic, number of called and total number of genes.

Supplementary dataset 5

For each 1 kb window we report the chrom, start, number of archaic windows, number of archaic windows which contain DAV-linked variants or DAV variant, diversity using all variants, diversityDAV-linked, diversityDAV, called bases, total individuals, recombinationrate, protein coding genes, amount of window covered by exons, B-value.

Supplementary dataset 6

Here we show the amount of archaic sequence found in the Icelandic population and in all non-African individuals from SGDP. We show the overlap of sequence along with the expected overlap by chance.

Supplementary dataset 7

Mutation spectrum comparison for 7-spectrum mutation type (fist tab) and 96-spectrum mutation type (second tab). The counts of derived alleles in archaic fragments and non-archaic fragments, the proportional ratio and the associated p-value from two-sided 10,000 permutation test (as explained in SI 6.3.2) are shown for each mutation type.

Supplementary dataset 8

In the first tab of the excel spreadsheet the Neanderthal genetic score for 271 phenotypes (145 quantitative traits and 132 case control phenotypes). The number of samples for each phenotype (or case and controls) are provided for each phenotype along with effect size and and p-value. The effect size and p-value are provided for both DAV SNPs and all SNPs. In the second tab we report 30 previously reported single nucleotide variants that showed an association to a phenotype. In the third tab we report the novel associations using the Decode data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skov, L., Coll Macià, M., Sveinbjörnsson, G. et al. The nature of Neanderthal introgression revealed by 27,566 Icelandic genomes. Nature 582, 78–83 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2225-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2225-9

This article is cited by

-

Evolutionary and functional analyses of LRP5 in archaic and extant modern humans

Human Genomics (2024)

-

More than a decade of genetic research on the Denisovans

Nature Reviews Genetics (2024)

-

A history of multiple Denisovan introgression events in modern humans

Nature Genetics (2024)

-

Ignoring population structure in hominin evolutionary models can lead to the inference of spurious admixture events

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

Genetic legacy of ancient hunter-gatherer Jomon in Japanese populations

Nature Communications (2024)