I enjoy it when conventional wisdom gets turned upside down. A good example appeared in The Federalist last week: David Breitenbeck’s Why Our Day Is Far More Religious Than The Middle Ages Was.

As someone who has studied Medieval philosophy and read St. Thomas Aquinas, I can attest that if ever there was an “Age of Reason,” it was the Middle Ages. Whereas hardly anyone today, outside of those who are classically educated, knows anything about logic. Read the whole essay, following the link. Whereupon I will question his definition of “faith.”

David Breitenbeck’s Why Our Day Is Far More Religious Than The Middle Ages Was:

The Middle Ages are often described as “the Age of Faith.” But surely, if any age deserves that epithet, it is ours.

True, the Middle Ages were the age of Christianity, but hardly the age of faith. If we take faith in the common, though oversimplified sense of blind belief in that which is not seen or understood, then the Middle Ages, with their worshipful admiration of Aristotle, fine definitions, and extremely precise use of language, and monasteries full of busy monks copying and commenting on scholarly texts, are the reverse of the age of faith.

An educated man in the Middle Ages might have believed in many things that we today would question, but he could tell us exactly why he believed them and cite both past scholarship and empirical observations in support of his ideas. An educated man of the postmodern age can only repeat what he’s been told must be true and assume you are in some manner a bad person if you question it. . . .

The postmodern world, by and large, receives Galileo’s discoveries, or those of Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Louis Pasteur, or any other scientist as articles of faith. They are true, and any doubts or questionings are not to be tolerated.

Try to explain to someone, for instance, the distinction between the Ptolemaic, Tychonic, Copernican, and Keplerian systems, or the major flaws in Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, and you will meet a blank wall of resistance, often coupled with snide implications against religious dogma. You see, you are now an infidel for questioning the Faith, and thus must be considered as one of the indistinguishable “bad people.”

Modern science does not proceed according to “reason,” as such; rather, it employs empirical observation as disciplined by the scientific method. Reason does come into play in the formulation and discussion of hypotheses. But the rationality is mainly that of mathematics rather than logical syllogisms, as used by medieval thinkers. (Seriously, if you want to see what someone can do with syllogisms and logical arguments applied to theology, read St. Thomas Aquinas. It is quite astonishing.)

But Breitenbeck is right that most people today know little about science. They treat scientists with the awe that medieval peasants reserved for priests. And they think of the engineers and inventors who turn scientific knowledge into technology as if they were magicians.

“Faith,” though, is NOT “blind belief in that which is not seen or understood,” as I think Breitenbeck realizes. (For various understandings of faith and how Christians have never understood it in this sense, see the Wikipedia entry on “Faith.”)

As Luther explains it, “Faith is a living, bold trust in God’s grace.” Furthermore, Luther writes, “faith is God’s work in us, that changes us and gives new birth from God. (John 1:13).”

Luther criticized Medieval theology precisely for its rationalism, that it looks to human reason as its authority as opposed to the revelation of God’s Word. And, indeed, notice the errors of its trust in reason, not only in theology but in science and many other areas. But the main problem with thinking that religion according to reason and reason alone (to use Kant’s phrase) is sufficient is that, as J. G. Hamann has shown in his “metacritique” of Kant is that reason itself relies on faith: faith in its premises; faith in logic; faith in the human mind, etc.

Faith requires an object. The key question is, what–or who–do you put your faith in? Is your faith in reason? Or, as I have heard TV preachers recommend, do you have faith in yourself? Or do you have faith in Jesus Christ, that He died for your sins and rose to give you everlasting life?

Misdirected faith, or faith in the wrong object, as Michael Lockwood has shown, is how Luther defined idolatry.

The Federalist‘s title for Breitenbeck’s essay says that our day is more religious than the Middle Ages. “Faith” does not equate to “religion,” as such. When the object of faith is Darwin, or global warming, or some politician, it wouldn’t seem to be a religious faith. Except that idolatry is a religion.

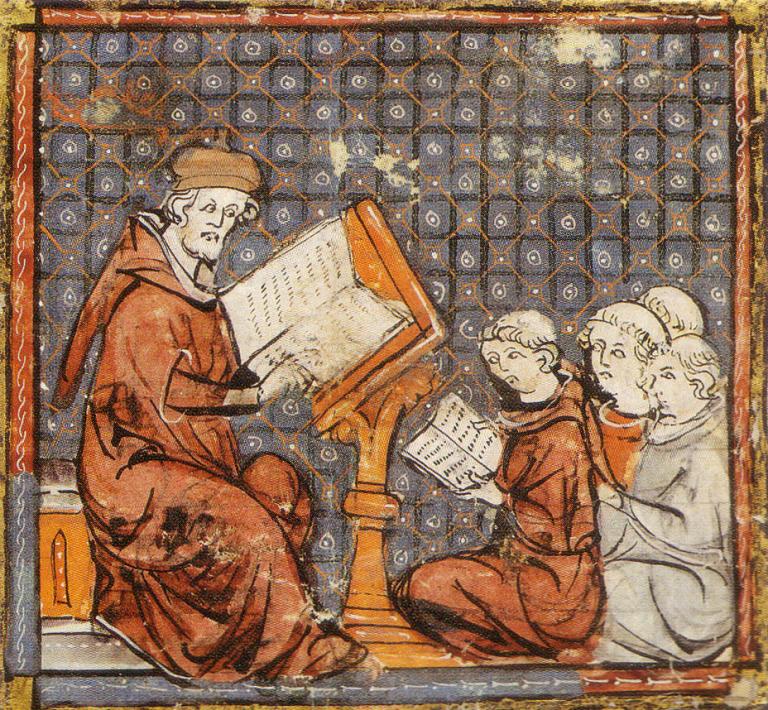

Illustration: “Cours de philosophie à Paris Grandes chroniques de France” (14th century) by Unknown (Castres, bibliothèque municipale) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons