Not long after blowing the lid off a National Security Agency-backed hacking group that operated in secret for 14 years, researchers at Moscow-based Kaspersky Lab returned home from February's annual security conference in Cancun, Mexico to an even more startling discovery. Since some time in the second half of 2014, a different state-sponsored group had been casing their corporate network using malware derived from Stuxnet, the highly sophisticated computer worm reportedly created by the US and Israel to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program.

Some of the malware's stealth capabilities were unlike anything Kaspersky researchers had ever seen, and in many respects, the malware was more advanced than the malicious programs developed by the NSA-tied Equation Group that Kaspersky just exposed. More intriguing still, Kaspersky antivirus products showed the same malware has infected one or more venues that hosted recent diplomatic negotiations the US and five other countries have convened with Iran over its nuclear program. Also puzzling: among the other 100 or fewer estimated victims were parties involved in events remembering the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.Developers planted several false flags in the malware to give the appearance its origins were in Eastern Europe or China. But as the Kaspersky researchers delved further into the 100 modules that encompass the platform, they discovered it was an updated version of Duqu, the malware discovered in late 2011 with code directly derived from Stuxnet. Evidence later suggested Duqu was used to spy on Iran's efforts to develop nuclear material and keep tabs on the country's trade relationships. Duqu's precise relation to Stuxnet remained a mystery when the group behind it went dark in 2012. Now, not only was it back with updated Stuxnet-derived malware that spied on Iran, it was also escalating its campaign with a brazen strike on Kaspersky.

"The last island of safety" ruined

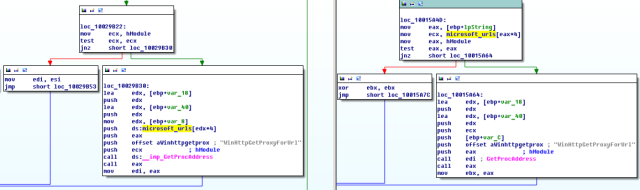

Duqu 2.0, as Kaspersky has dubbed the 2014 version, used at least one "zero-day" in Windows that Microsoft patched only Tuesday. It very possibly used two other Windows flaws that weren't publicly known or fixed by Microsoft until late last year, well after the attackers first penetrated Kaspersky's network. The infection originated in a computer used by a non-technical Kaspersky employee located in one of the company's satellite offices in the Asia-Pacific region. Company officials still don't know precisely how the machine was compromised because attackers wiped the browsing history and e-mail stored on the machine in the hours after researchers identified it as the attackers' entry point.

Because the rest of the data remained intact on the PC and its security patches were fully up to date, researchers suspect the employee received a highly targeted spear phishing e-mail that led to a website containing a zero-day exploit. Kaspersky investigators said the unpatched vulnerability of the PC may be CVE-2014-4148, which attackers had been exploiting in the wild in the weeks or months prior to Microsoft patching it in October. The flaw resided in the TrueType font parsing engine of Windows and made it possible to execute malicious code using a booby-trapped Office document. It is eerily similar to CVE-2011-3402, another TrueType Windows vulnerability Kaspersky has confirmed was used to infect targets of the 2011 version of Duqu.

However the Asian-Pacific computer was compromised, forensic evidence suggests that the attackers went on to exploit a separate critical vulnerability in Windows server versions that allowed the compromised PC to hijack the Windows domain controllers Kaspersky engineers used to administer the huge fleet of computers on their network. Microsoft issued an emergency update in November that patched the domain controller vulnerability after warning it was being used in highly targeted attacks. By then, however, it was too late. The attackers were already hunkered down inside Kaspersky's corporate network with the ability to install their arsenal of malicious software on just about any machine they wanted.

Eureka moment

Kaspersky officials first became suspicious their network might be infected in the weeks following February's Security Analyst Summit, where company researchers exposed a state-sponsored hacking operation that had ties to some of the developers of Stuxnet. Kaspersky dubbed the highly sophisticated group behind the 14-year campaign Equation Group. Now back in Moscow, a company engineer was testing a software prototype for detecting so-called advanced persistent threats (APTs), the type of well-organized and highly sophisticated attack campaigns launched by well-funded hacking groups. Strangely enough, the developer's computer itself was having unusual interactions with the Kaspersky network. The new APT technology under development, it seemed, was one of several things of interest to the Duqu attackers penetrating the Kaspersky fortress.

"For the developer it was important to find out why" his PC was acting oddly, Kamluk said. "Of course, he did not consider that machine could be infected by real malware. We eventually found an alien module that should not be there that tried to mask behind legitimate looking modules from Microsoft. That was the point of discovery."

Company researchers spent the following weeks conducting detailed forensics on the entire Kaspersky network and combing through its vast database of malware samples for people outside Kaspersky's perimeter who also fell victim to this newly created version of Duqu. What they found was a vastly overhauled malware operation that made huge leaps in stealth, operational security, and software design. The Duqu actors also grew much more ambitious, infecting an estimated 100 or so targets, about twice as many as were hit by the 2011 version. Kaspersky published the results of the investigation so far Wednesday in a nearly 50-page report titled The Duqu Bet: Technical Details.

In a report published Wednesday shortly after Ars published this article, researchers from Symantec said the same malware that hit Kaspersky infected several other companies in what appeared to be attack campaigns against a small number of selected targets. They included one telecommunications operator in Europe, another telecoms operator in North Africa and a South East Asian electronic equipment manufacturer. Infections also hit organizations in the US, the UK, Sweden, India, and Hong Kong.

"Based on our analysis, Symantec believes that Duqu 2.0 is an evolution of the original threat, created by the same group of attackers," the researchers wrote in the report. "Duqu 2.0 is a fully featured information-stealing tool that is designed to maintain a long term, low profile presence on the target's network. Its creators have likely used it as one of their main tools in multiple intelligence gathering campaigns."

In all, "dozens" of machines inside Kaspersky's network were infected. Researchers spent time observing live Duqu attackers as they manually traversed various company machines in search of research, intellectual property, and other proprietary information. Company officials were unable to provide Ars with an estimate of how many megabytes or gigabytes of data were extracted from their network, in part because the custom network connections Duqu used may have bypassed normal logging procedures. The company hasn't ruled out the possibility the attackers obtained Kaspersky Lab source code, but there are no signs they tried to compromise any of Kaspersky's 400 million users.

"For a period of time we were able just to monitor what they were doing and just to watch their movements and try to learn more about how they operate," Costin Raiu, director of Kaspersky Lab's global research and analysis team, told Ars. "We were able to do that and eventually I guess they figured out that we knew and that we were watching them so they went away. But for a period of time, we were able to watch them working, like playing in the network, trying to attack other computers. So we were watching on them trying to spy and that's how we know when they were active."

Watching the detectives

The surveillance by the attackers, the monitoring of that surveillance by Kaspersky, and ultimately, the attackers discovering they were being watched led to some tense moments. As the Kaspersky researchers arrived at the conclusion that the Asian-Pacific PC was the attackers' initial point of entry, it didn't take long for the attackers to learn of this crucial break in the investigation. Almost immediately, the e-mail and browsing history of the infected computer were permanently wiped, frustrating for investigators' current attempts to learn exactly how the machine had been compromised. Since the rest of the hard drive data remained intact, Kaspersky officials suspect the fully patched PC was hit by a Web-based zero-day exploit that was triggered through a spear-phishing e-mail.

If the PC was a smoking gun that would provide crucial clues about the attack and the people who carried them out, the data wipe was the digital equivalent of the guilty party kicking the evidence into a river before the investigators could retrieve it. For the time being, those important details aren't available, but Raiu said he's hopeful they will surface eventually.

"When we are done with reviewing all this information, I'm confident we will find the entry point," he said.

reader comments

167