The Appropriations Committee of the US House of Representatives has set May 8 as the date they will begin debating an election year budget that pares NASA back to its lowest level as a percentage of the Federal budget since 1959, surpassing last year's record low of 0.48%. In absolute terms, it will roughly match the 2006 Bush levels, cutting money from the Space Technology and Commercial Crew program requests for a third year and adding money to the Space Launch System and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle, two House favorites.

The Congressional Space Program

The House budget contrasts with the Senate budget, which also cuts money from the $830M Commercial Crew budget request but decreases NASA's budget somewhat less in absolute terms. The House also conflicts with the Senate in oversight of the Commercial Crew program, in that the House attempts to direct NASA to narrow the current field of four manned spacecraft to a single "competitor." The Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle is already contracted to Lockheed-Martin, and many on the Hill would like to see NASA hand the Commercial Crew vehicle for ferrying astronauts to the International Space Station to Boeing.

The report accompanying the new budget bill from the House's Commerce, Justice and Science committee calls NASA's estimated development costs on the four vehicles competing to ferry crew to the Space Station ($4.86B) "too high". After the Space Station's life was shortened by the Bush administration, which would have had it re-enter the atmosphere in 2015, one of the first acts of the Obama administration was to extend the Station to at least 2020. The report points out that the vehicles might only service the Space Station a few years before the Station is forced to re-enter the atmosphere.

The report also raises the concern that the Federal Government is not protecting its own intellectual and physical property, should one or more competitors leave the competition and strike out on its own. It is difficult to discern which one of the companies might be the target of this concern, given that all four, Boeing, SpaceX, Sierra Nevada, and Blue Origin, have designed and developed their own vehicles.

Pick a winner now to avoid picking the wrong winner later

After raising the intellectual property issue, the report compares the Commercial Crew program to the failure last year of solar energy firm Solyndra, which failed in part due to the drastic recent decrease in the cost of natural gas. Solyndra's capital loans were guaranteed by the Federal Government, but no such loans or guarantees have been made in the case of the four Commercial Crew competitors, which are mostly self-funding—NASA contributes as a partner. Funding to the four vehicles in the Commercial Crew program for the last three years to date has been $830M. In contrast, the Orion Multipurpose Crew Vehicle is funded this year at $1.5B.

The solution, according to the report, is to abandon the competition and pick a winner. “The Committee believes that many of these concerns would be addressed by an immediate downselect to a single competitor or, at most, the execution of a leader-follower paradigm in which NASA makes one large award to a main commercial partner and a second small award to a back-up partner."

Boeing has been mentioned in hearings as the preferred company by many in the House despite that it is at least one year behind SpaceX in vehicle development. The weakest competitor is Sierra Nevada, with a vehicle that is a reincarnation of the NASA HL-20 vehicle designed for servicing the Station, so it seems likely that NASA would choose Sierra Nevada for the small award in a leader-follower paradigm. But that vehicle is also being produced by Boeing as Sierra Nevada's largest subcontractor, leading to an interesting position wherein Boeing would be both the leader and the follower.

Desperate times lead to Space Act Agreements

Last year, because of Congressional underfunding, NASA was forced to use Space Act Agreements instead of the traditional, and more stringent, Federal Acquisition Regulation system to fund its Commercial Crew efforts. According to a statement Administrator Charlie Boldeny, NASA would have only been able to fund one company with the $406M it received last year in lieu of its $829M request. By using Space Act Agreements, which are also far less costly, it was able to stretch that budget to four companies.

The admission was curious in that it gave proof that Space Act Agreements allow NASA to get far more for its taxpayer dollars. Despite the resourcefulness, however, domestic U.S. access to the Station was delayed by another year to 2017.

In this year's budget request, NASA stated that it would again be using Space Act Agreements to manage the 2013 Commercial Crew Program. The House budget report strongly encourages NASA to move away from SAA's, but stops short of attempting to make it law.

Heavy lifting

The biggest curiosity in the space business is currently the Space Launch System, labeled by many as the "Senate Launch System" because NASA seems to have been forced to take a rocket they didn't specify and don't want. Both the House and the Senate require the Space Launch System by law to have the capability to lift 130 metric tons to orbit, even though no mission exists yet for the giant rocket and no one is sure that one will exist for the forseeable future.

The SLS is so expensive that NASA will only be able to afford to launch it every two years at best, giving rise to a strong suspicion that the rocket will be cancelled before completion. In attempt to spare all parties from further embarassment, the new House bill orders NASA to come up with a list of possible missions and destinations for SLS.

All the currently proposed missions could be accomplished with existing (and much cheaper) rockets, provided that NASA is able to start its planned use of orbital fuel depots for refueling. The SLS retains strong support in Congress, where it originated, and so the House bill this year requires quarterly reports on the state of the Space Launch System to make sure that it is making proper progress.

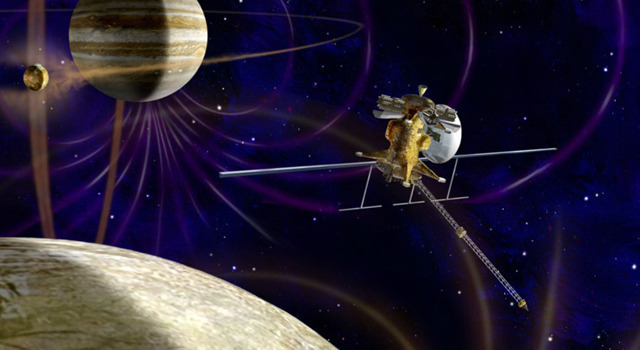

The last curiosity in the House budget is that it could potentially force NASA to explore Europa, Jupiter's watery moon and potentially the best place other than Earth to find new life. After withdrawing its support for the joint U.S.-European ExoMars program earlier this year amidst a hail of criticism, NASA proposed a new integrated (and putatively lower-cost) strategy entitled "Mars Next Decade."

The House bill increases the funding for Mars Next Decade by $88M, and mandates that the National Research Council must certify that Mars Next Decade will return a sample of Martian soil to the Earth. If the NRC is unable to make this guarantee, NASA must "(1) notify the Committees; (2) reallocate the funds provided for Mars Next Decade to the Outer Planets Flagship program in order to begin substantive work on the second priority mission, a descoped Europa orbiter (considered in the 2011 Planetary Decadal Survey; and (3) submit the Mars Next Decade mission concept, or any substitute Mars mission concept, for competition in the Discovery or New Frontiers programs."

Congress will begin debating the new bill shortly before SpaceX hopes to launch its first attempt to berth a Dragon spacecraft with the International Space Station. That launch has now slipped to May 10. Still, next week will be an exciting one for space exploration advocates, as will the entire year.

reader comments

14