"We don't have a requirement to build anymore" says Olympic Games director

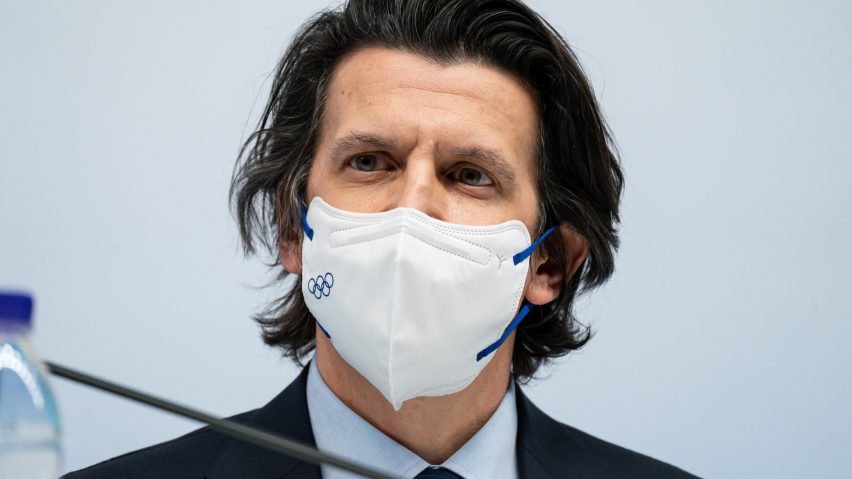

Few permanent buildings will be built for the Olympics in future, with events set to be hosted in existing structures and temporary venues instead, says Olympic Games executive director Christophe Dubi in this exclusive interview.

Building large numbers of new venues for the Olympic Games is a thing of the past, as organisers aim to limit the environmental impact of the global sporting events, Dubi said.

"The intention is to go where all the expertise and venues exist," he told Dezeen, speaking from Beijing.

Previously, host cities have commonly constructed several ambitious arenas and sports centres, taking the opportunity to exhibit their ability to undertake major infrastructure projects on a global stage.

But only a handful of venues were built for the ongoing Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, continuing a theme from other recent Games.

A long-track ice skating arena was designed by Populous and a pair of ski jumps were created, with the city reusing multiple venues built in the city for the 2008 Olympics.

"We don't want to force hosts into building venues"

This continues a strategy for reuse that saw many events at last year's Tokyo Olympics hosted in venues built for the 1964 Olympics. Dubi and the Olympic organisers will continue placing an emphasis on existing buildings at future games, he said.

"It simply makes sense because we have a pool of potential organisers that is finite," said Dubi, who is tasked with overseeing the delivery of the Olympics.

"So why don't we go to the regions that have organised the games in the past or have organised other multi-sports events, hosting world cups and world championships?" he continued.

"We don't want to force hosts into building venues that you're not certain you can reuse in the future."

No demand "for a crazy amount of new building"

While only a handful of venues were built for Beijing 2022, even fewer are set to be constructed for some of the upcoming Olympic Games.

Dubi explained that "only one new venue will be built" for the Milano Cortina Olympics in 2026, while "zero new venues" will be built for the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028.

Given the focus on reusing existing structures, Dubi doesn't believe that we will see Olympic parks full of new buildings, like those created for the Sochi, London, Athens and Sydney games, ever be built again.

"I don't think we'll see that [entire Olympic campuses built] in the foreseeable future," he said.

"The reason being, I don't think the expectations of a given community at this point in time, or in foreseeable future, is for a crazy amount of new building."

"Virtually any city can host the games"

Dubi argues that rather than limiting the number of cities able to host the games, focusing on existing venues combined with temporary structures can expand the number of potential host cities.

"We don't have a requirement to build anymore, so virtually any city can host the games," he argued.

He envisions host cities making use of temporary structures, like the volleyball venue on Horse Guards Parade at the London Olympics in 2012 or the skateboarding venue in the Place de la Concorde at Paris 2024, alongside existing permanent venues.

"What we will see is a crazy amount of [temporary] fields of play," he said.

"We'll see probably temporary stadiums of up to 40,000. So certainly more fields of play, more leisure opportunities for communities, but probably not a huge amount of new stadiums."

For specialist facilities such as ski jumps, he suggests that hosts could use venues in other cities or even other countries, citing the equestrian events at the Beijing 2008 Olympics, which were hosted in Hong Kong, and the surfing at Paris 2024, which will be hosted in French Polynesia.

"Say you're bidding for the games and you don't have a specific venue, we will simply say go elsewhere, it's going to be just fine," he explained.

"We have one currently in the south of Europe that is thinking about [hosting a Winter] Games – they don't have ski jump or a bobsled track."

Overall, Dubi expects future organisers to be innovative and incorporate a city's existing architecture into plans for the games.

"If in the future, instead of having a temporary wall for sports climbing that is made out of nothing, if we can use one of the buildings in the city, well, let's use it," he said.

"That's what we're going to be looking for from organisers: be original, innovate, use what you have, what defines you as a city, as a community."

Read on for the full interview with Dubi:

Christophe Dubi: My role is to oversee and hopefully contribute a bit to first, conceiving any addition of the games, and then up to the delivery and the learnings of every addition.

It's a continuous cycle of what you've learned and what you can embed in the next edition. I was in charge of the commission that did the evaluation of these games here seven years ago. So starting from very baby steps when you discuss the vision until it materialises and is being delivered, like, we are now in the trenches during operations time.

Tom Ravenscroft: What was the thinking behind choosing Beijing to host this edition of the Olympics?

Christophe Dubi: Three things. One, which is not linked to architecture is the development of winter sports and what it means for China and for the rest of the world. This was number one because in Asia we've been in Japan for winter, we've been in Korea for winter, never in China and the whole north of China is incredibly cold.

You have a very active winter sports movement with a lot of potential for development. So we saw that as one of the future legacies.

When it comes to architecture, we have a game in winter that could reuse some of the 2008 solutions. From an architectural standpoint, those landmarks, like the Bird's Nest and the Aquatic Centre, remain icons in sports and architecture in general.

The possibility to reuse them and more than a decade later is a sign that they were well designed, well built, and well maintained.

At the same time, we needed new venues because they simply didn't have them. A bob and luge track and sliding centre they did not have across China. They didn't have any ski jumps. They didn't have a long track for skating. They have plenty of ice rinks. They are great in figure skating and superb in short-track but not long-track.

Tom Ravenscroft: How have Olympic venues evolved since 2008 and what lessons have you learnt from previous games?

Christophe Dubi: I think it's a sign of the times. The games always adapt to society and we are a magnifying glass of society at any given point in time. Take the example of last summer where mental health came to the forefront because of a number of athletes speaking out, and they were incredibly brave in Tokyo.

Mental health for years is something that exists. But everybody was pretty shy to speak about, and you don't really want and suddenly, because of these athletes coming to the forefront, it becomes mainstream.

And I think it's the same for architecture, here you are in the 2000s, where it has to be to be big, it has to be spectacular. While in the 2020s, it has to be probably much more subdued. And it's very fitting in this context as well.

Where the president of the country is speaking about these games always said that, yes, they have to be perfectly organised games, but at the same time, they have to be somewhat modest with, with inverted commas, because what we said before simply the size and you know, more modest. Modest for China.

We see more green buildings, we see more flat roofs with gardens and now it's even against the walls and these are the kind of things that you see now across Europe, in Milano and elsewhere and for sure, you will have that as well the Olympic venues.

Tom Ravenscroft: So you're saying it's a reflection of society, but should the Olympics lead the conversation on architecture and sustainability?

Christophe Dubi: You cannot escape because when you have such a big platform you cannot shy away from your duties and responsibility.

You cannot remain outside of the public debate because if you don't lead on some of these issues, expectations will be placed on you and if you don't talk about it and be transparent about them someone will place words and intentions on this organisation.

So yes, the Olympic games have a duty to be at the forefront and there are many things that the organising committees and the IOC for that matter are doing. You know our headquarter was for a very long time on the number of standards including BREEAM and others, we were the top-notch administration building in the world. Now it's been two or three years so I don't know whether it's still the case. You see we cannot be third.

Tom Ravenscroft: With the architecture, is this the least number of venues that have been constructed for an Olympics?

Christophe Dubi: We are having the smallest in Milano Cortina, which are games for which only one new venue will be built. And it's a multi-sport venue in the south of Milan, which will be used for ice hockey, but other purposes afterward.

The intention is to go where all the expertise and venues exist.

It simply makes sense because we have a pool of potential organisers that is finite right? So why don't we go to the regions that have organized the games in the past or have organised other multi-sports events, hosting world cups and world championships.

We don't want to force regions into building venues that you're not certain you can reuse in the future.

A ski jump, unlike an ice rink, only ski jumpers can use. So you don't want to force a future host in 2030 or 2034 to build the venue if it's not absolutely needed for especially community purposes, you want to make sure that everything you do can be used by the top athletes, but also by the general public.

So say you're bidding for the games. And if you don't have a specific venue, we will simply say go elsewhere, it's going to be just fine.

We have one currently in the south of Europe that is thinking about games – they don't have a ski jump or a bobsled track.

In 2008 we organised the equestrian in Hong Kong, and it was okay. It was still the Beijing Games, but it was in Hong Kong.

Tom Ravenscroft: So you are looking for creative solutions. You don't expect cities to build every venue anymore. Do you think we'll ever see another Athens or Sydney where all the venues are built from scratch?

Christophe Dubi: I don't think we'll see that in the foreseeable future. And the reason being, I don't think the expectations of a given community at this point in time, right here right now, or in foreseeable future is for a crazy amount of new building.

What we will see is a crazy amount of fields of play, because leisure, especially leisure in urban environments is incredibly important.

We'll see probably temporary stadiums of up to 40,000. So certainly more fields of play more, more leisure opportunities for communities, but probably not a huge amount of new stadiums.

Tom Ravenscroft: Do you foresee an Olympics where nothing new is built?

Christophe Dubi: In Los Angeles, we will have zero new venues.

Tom Ravenscroft: Will that become the benchmark, where you really have to justify building anything?

Christophe Dubi: Let's look at it differently. If I asked you what are your best memories out of a given Olympic Games? Is it a visual imprint of a stadium? Or is it the emotion of an athlete's reaching out to another or a moment in an opening ceremony?

Our business is the business of emotions. And sometimes the visual impression helps. But the raw material, the most powerful one is the human.

We will still create incredibly powerful stories in any location when human beings are writing something special. Sometimes it can be the beauty of a segment of an opening ceremony. Sometimes it's on the field of play, others it can be volunteers, helping someone in the industry. And sometimes it is the Bird's Nest that radiates at night.

Tom Ravenscroft: So the architecture is a supporting actor?

Christophe Dubi: I wouldn't rank in this order, when I can say is that the first impression that, that you get entering the Bird's Nest in Beijing is that it is something special. And what happens here is bound to be special because this venue is in. So you know, I cannot say it's first or second. Yeah, it's all part is that you can create incredible things out of nothing.

But if you have something very special like that, for sure. It's very conducive to creating something special from the start. Everybody can just jump in quickly. I think everybody's entry point is different.

Tom Ravenscroft: So what will be the legacy of these games then? How will create a legacy in a city like LA when there aren't going to be any new buildings?

Christophe Dubi: Two things. The first is you create a physical legacy if it is needed. So if LA considers that they don't need new venues, and you have a sufficient number for the games, why create a legacy that is not helpful to again a community that's the main thing because you cannot now conceive the venue just for the sake of elite athletes, which is fantastic.

They inspire us, but at the same time, you have to make sure that you have greater use and the community so do not create something that is not needed. A venue like Horseguards Parade, which was a full temporary venue, does not have a lesser legacy in the mind of people that a newly built purpose venue.

Paris is a city where you don't want to build too much because you want to make sure that you use the city backdrop as your venue.

And building an urban park with skateboarders on Place de la Concorde, where you have, to your left, looking from the south you have on your left the Eiffel Tower, and on the other. It is a temporary venue that also will have a formidable legacy.

And it's all around the built environment, except that you don't deal new, using what is good, what is part of the history and the culture of that host community to make an impression and a legacy for you and for me, okay, so the approach,

Tom Ravenscroft: So the aim is to use the architecture without having to build new architecture?

Christophe Dubi: Correct. If in the future, instead of having a temporary wall for sports climbing that is made out of nothing, if we can use one of the buildings in the city, well, let's use it.

Okay, so that's what we're going to be looking for from organisers be original, innovative use, what you have, what defines you, as a city as a community. And let's create this together that visual impression that that souvenir that is set in stone.

We're not against building because Sochi is incredibly successful now winter and summer, because they needed to get some of the winter fans, not necessarily across in Switzerland and France, which is probably a bit of loss.

But to also stay in Russia, they didn't have any, any real great resort. Now they do have one and it's incredibly used. And it's the same here in China, it would have been wrong for us to say you're not allowed to build. But when you build it has to make sense.

Tom Ravenscroft: So not having a ski jump is not going to exclude you from hosting.

Christophe Dubi: Correct. If the Chinese would have said, by the way, we want to go elsewhere for the ski jumps we would have said, fine. Good. Tahiti will do surfing for Paris? Okay. Right. With the best wave in the world, most powerful.

Tom Ravenscroft: Do you ever see a point when one city will become the permanent host?

Christophe Dubi: No, because what makes this is the diversity. It's the inclusivity it's the arms wide open. It's games which are for everyone. What we were doing in having the games moving from one area to the other is to show how rich and diverse is the world. And our great it is when the world comes at one in one location,

Tom Ravenscroft: And how do you justify moving on a sustainability level?

Christophe Dubi: Because we don't have a requirement to build anymore, so virtually any city can host the games. And I dream to see the games coming to a continent that never hosted them. The first Youth Olympic Games will be in Dakar in 2026. And this is brilliant.

Tom Ravenscroft: Will there be a Winter Olympics in Africa?

Christophe Dubi: You could envisage one in the southern hemisphere, you could imagine Argentina, or actually New Zealand, it would just be a little bit of an upset to the calendar?