Curiosity rover sees seasonal Mars methane swing

- Published

It may only be a very small part of Mars' atmosphere but methane waxes and wanes with the seasons, scientists say.

The discovery made by the Curiosity rover is important because it helps narrow the likely sources of the gas.

On Earth, those sources largely involve biological emissions - from wetlands, paddy fields, livestock and the like.

No-one can yet tie a life signature to Mars' methane, but the nature of its seasonal behaviour probably rules out some geological explanations for it.

"For the first time in the history of Mars methane measurements, we have something that's repeatable," said Dr Chris Webster, a US space agency (Nasa) scientist working on Curiosity.

"It's like trying to find a fault on your car. If it's intermittent you can never solve it, but if you've got some repeatability you've got some chance of understanding it," he told BBC News.

Methane in Mars' atmosphere is a fascinating topic. The gas is short-lived so the fact that it persists in the planet's air points to a constant, on-going source - and given CH₄'s link to biology on Earth, scientists need to get to the bottom of this martian mystery.

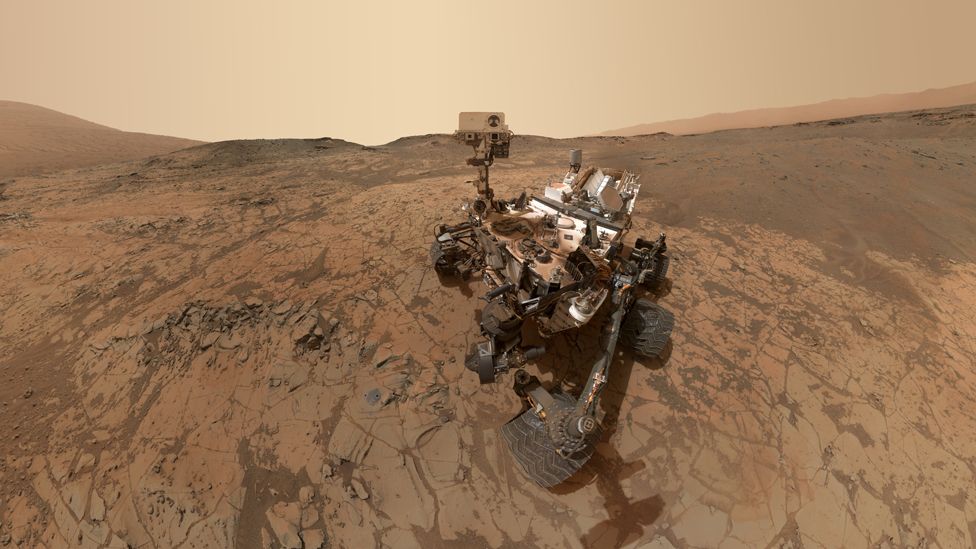

Ever since it landed in the Red Planet's equatorial Gale Crater in 2012, Curiosity has been sniffing the air for methane.

The roving robotic laboratory has seen wafts where the concentration has risen upwards of seven parts per billion (ppb) (by comparison, on Earth it is about 1,860ppb). But over the past few years, the one-tonne vehicle has also been tracking the general background trend.

It is this behaviour that Dr Webster and colleagues report in Science Magazine this week.

They show methane rises from just above 0.2ppb in the northern hemisphere winter to a fraction over 0.6ppb in the summer.

The team's best explanation is that methane is seeping up from underground, perhaps from stored ices, and is then being released when surface soils are warmed.

The team cannot positively identify the origin of the methane, but the researchers think they can close down one particular mechanism for its production.

This involves sunlight breaking up carbon-rich (organic) molecules that have fallen to the planet's surface in meteorites.

The variation in ultraviolet light over the course of the seasons is not big enough to drive the scale of the change seen in the methane concentration, says Dr Webster.

"We know the intensity of the Sun and this mechanism should produce only a 20% increase in methane during the summer, but we're seeing it increase by a factor of three," he explained.

All this leaves open the question of what type of sub-surface reservoir is feeding the release - whether it derives from some other geochemical process or is the product of microbial activity; whether it is newly minted methane or some ancient store.

"We can't distinguish; but importantly we still can't rule out a biological contribution," Dr Webster told BBC News.

The European Space Agency (Esa) has a new satellite at Mars known as the Trace Gas Orbiter. This started a global search for methane in the atmosphere during the past fortnight.

It is possible the probe might be able to detect places on the planet where the gas is being emitted in larger quantities.

If such a location can be identified, some future mission could then visit it with the sensitive analytical tools needed to determine whether the CH₄ is the kind normally associated with life. On Earth, biology has a preference to incorporate the lighter form of carbon atom when making the molecule.

Tough molecules

A second paper published in the same edition of Science Magazine describes some of the new types of organic molecules that Curiosity has found inside Gale Crater's rocks.

Once again, like methane, organics are not a direct indicator of life - but life cannot exist without such molecules, DNA and proteins being good examples.

The story of organics on Mars is therefore of enormous interest if the presence of life is to be confirmed, if only in the long-distant past.

The Curiosity team has previously reported pretty simple carbon-rich compounds - what are termed chlorinated hydrocarbons because of their inclusion of chlorine atoms in their carbon-hydrogen structures. The new molecules, drilled from three-billion-year-old mudstones that were laid down in a lake environment, are more diverse and more complex.

They include thiophenes, which are a class that have sulphur atoms bonded into their structures; and that is important because the sulphur aids preservation.

If, as the team believes, the molecules Curiosity is seeing are mere fragments of much larger forms, this bodes well for those future missions that can drill deeper into the planet's surface. An Esa rover aims to do just this in 2021.

"ExoMars is going to go deep - 2m deep," explained the Science paper's lead author, Dr Jennifer Eigenbrode. "That gives it the possibility of encountering rocks that have not been exposed to any significant (degradation from) ionising radiation at the surface.

"ExoMars has a chance of discovering extant life. But, even if it doesn't, just understanding the change of organic matter from the surface to what's at depth is going to be hugely revealing.

"I've no doubt that humans when they get to Mars are going to want to try farming. And if they do, they're going to need a source of organic matter," she told BBC News.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos