It is no surprise that many teachers have an interest in neuroscience and psychology since areas such as memory, motivation, curiosity, intelligence and determination are highly important in education.

But neuroscience and psychology are complex, nuanced subjects that come with many caveats. Although progress is being made towards understanding what helps and hinders students, there is still a disconnect between the research in labs and what happens in many schools.

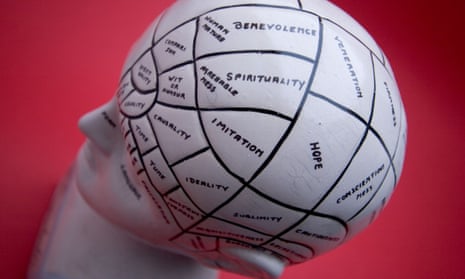

Many “neuromyths” are rampant in our classrooms, and research suggests that people are often seduced by neuroscientific explanations, even if these are not accurate or even relevant. Research also shows that explanations accompanied by images of the brain also persuade people to believe in their validity, however random the illustration.

Lia Commissar, a project manager at the Wellcome Trust, says there are several reasons why neuromyths gain traction: “They seem to persist because they are easy to understand, fit everyday observation, are heavily promoted or are easy to implement. However, unfortunately they often have little or no evidence supporting the impact they will have on learning.”

Such myths are a drain on time and money, and it is important to explore and expose them. So which popular neuromyths exist in schools and how did they catch on?

Learning styles

The myth: Learning styles are often referred to as VAK – students are categorised as visual, auditory or kinaesthetic learners. This myth states that students will learn more if they are taught in a way that matches their preferred style. Despite an absence of any evidence (pdf) to support this claim, research carried out in 2012 found it was believed by 93% of teachers in the UK.

How it caught on: Each student is unique and has a different personality, experience and genes. Teachers are often encouraged to differentiate to ensure that each child is making as much progress as they can. This, combined with the fact that students may have a preference for how they are taught, has morphed into the belief that if you match your style to their preference, it will lead to better grades.

Where next for learning styles? Teacher Tom Bennet recently drew attention to the problem of this myth being taught in initial teacher training. On Twitter, and the hashtag #VAKOFF has been used to draw attention to this neuro-nonsense. To highlight the lack of evidence behind this myth, $5,000 has been promised to anyone who can prove any such intervention helps. Advances in research may help kill this myth, with findings indicating that teaching new information to students using a variety of senses results in stronger learning (pdf).

You only use 10% of your brain

The myth: This myth states that people only use 10% of their brain. In a survey of the general public in Brazil (pdf), this brain myth was one of the most prevalent. But it is completely untrue. We are able to examine the brain in better detail than ever before; if we were only using 10% of it, at least one scientist would have written about it but none has.

The origins: Many people believe Albert Einstein first said this. He didn’t. In fact, he didn’t say most of the things that the internet claims he did. This myth is alluring as it resonates with the very true fact that we can probably get better at things and our potential is an unknown entity.

Where next for the 10% myth? Hopefully, the overwhelming evidence against this myth will drown it out. Unfortunately, as long as it keeps being linked to the concept of self-improvement and bettering yourself, it will probably hang around for some time yet.

Right brain v left brain

The myth: 91% of teachers believe that difference between the left hemisphere and right hemisphere explains individual differences among learners. This typically translates into people thinking you are left-brained if you are rational and objective or right-brained if you are intuitive and creative.

The origins: In the 1960s, research on patients with epilepsy found that when the connection between the right and left hemispheres were broken, the two sides acted individually and processed things differently. This led to the belief that the two hemispheres of our brain worked independently. This spoke to the desire for us to categorise people and behaviours. It made the complex simple; the confusing clear.

Where next for the right-brain/left-brain myth?

Researchers have found that neither hemisphere is solely responsible for one type of personality. It is a particularly damaging myth as it can lead to students not trying in certain subjects as they believe they don’t have the brain for it.

Playing brain games makes you smarter

The myth: That playing brain-training games can help improve your memory, concentration or intelligence. This is usually evidenced by people playing these games and getting better at them; however, the problem is that there is little to no transfer of these skills when tested in different contexts (ie in the classroom).

The origins: This myth is mainly peddled by companies wanting to cash in on the public’s interest in neuroscience. They may be fun to play, but research shows that popular brain games do not make you smarter or improve your thinking.

Where next for the brain game myth? There may be some benefit for a small percentage of the population (early research suggests it may be of benefit in the fight against Alzheimer’s). However, one of the lead researchers into brain training games has concluded that there is “no evidence for any generalised improvements in cognitive function following brain training in a large sample of healthy adults”.

Why teachers need a critical eye

The fields of psychology and neuroscience can aid us in helping students, but it is important to view claims with a critical eye. Is the claim being sold as a silver-bullet? What is the evidence behind it? Does it sound too simple? Hopefully, as these myths die out, they can be replaced with practical suggestions to best help students, that are backed up by credible research.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion