Texas’ maternal death rates top most industrialized countries

HOUSTON – Pregnant women visiting the Center for Children and Women get more than ultrasounds and vitamins. They get blood pressure checks, mental health screenings, diabetes tests and lab work – all under one roof.

The clinic is on a frontline mission to reverse a disturbing trend in Texas: Women in the state are dying of pregnancy-related ailments at a higher rate than the rest of the country and even most other industrialized countries. And no one’s sure exactly why.

“This is an incredibly important issue that needs urgent attention,” said Lisa Hollier, the center’s medical director and head of the state’s Maternal Mortality and MorbidityTask Force.

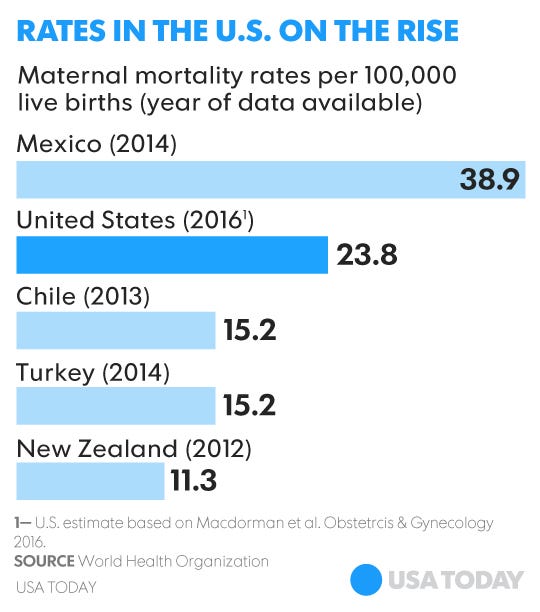

The rate of maternal mortality in Texas spiked from 18.6 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010 to more than 30 per 100,000 in 2011 and remained over 30 per 100,000 through 2014, according to a recent study in the medical journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. That’s significantly higher than Italy (2.1 deaths per 100,000 live births), Japan (3.3) and France (5.5), and more in line with Mexico (38.9) or Turkey and Chile (15.2), according to World Health Organization statistics.

Across the USA, the rate of maternal deaths also jumped from 18.8 per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 – a 27% jump, the study showed.

Maternal deaths are still relatively rare. Texas, for instance, tracks about 150 deaths a year out of around 400,000 live births. But the rate of increase and the fact that the numbers are rising in the USA while dropping in other industrialized countries is cause for alarm, said Eugene Declercq, a professor and assistant dean at Boston University School of Public Health and co-author of the study.

“We are so far behind these other countries, there’s clearly a problem here,” he said. “There’s real reason to be concerned.”

Causes of maternal deaths in Texas range from cardiac events to hypertension, drug overdose and suicide, according to a report released earlier this year by the Texas task force. The report, which looked at deaths in 2011 and 2012 associated with pregnancy and within a year after giving birth, also found that African-American women were disproportionately more likely to die in pregnancy-related deaths than white or Hispanic women.

Black women accounted for just 11% of all births in Texas, but they made up 29% of maternal deaths, according to the Texas report. Hispanic women accounted for nearly half – 48% – of all births, but made up 31% of maternal deaths.

Why Texas women died from seemingly preventable ailments – and why African-American women are more likely to be affected – remains a mystery, said June Hanke, a task force member and analyst with the Harris Health System in Houston.

The task force combing through the Texas deaths for more clues. “We’re just getting started,” she said.

Some experts point to the state’s cut of family planning services and refusal to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act as possible reasons. In 2011, Texas lawmakers slashed the family planning budget by more than $70 million and, two years later, greatly reduced the number of abortion clinics in the state by mandating they meet ambulatory surgical center standards and employ doctors with admitting privileges at hospitals. The Supreme Court this summer ruled against the abortion restrictions.

But the family planning service cuts didn’t kick in until September 2011 and don’t account for the sharp spike in maternal deaths logged at the beginning of that year, Hollier said. The cuts in health care may have contributed, but are not the sole culprit, she said.

George Saade, head of obstetrics at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, was so alarmed by the rise in maternal deaths in Texas in recent years that he co-wrote a paper in Obstetrics and Gynecology four years ago, warning of the trend and calling for changes.

Growing obesity in Texas women and increased cases of hypertension and other ailments while pregnant make them a health risk unlike any seen in recent years, he said. A thorough regimen of mental and physical screenings before, during and after pregnancies is needed to make sure women stay healthy for births – and beyond, he said.

“We have to accept that pregnant women these days are more complex and at risk than before,” Saade said. “We can’t follow the care we did 50 years ago and hope it’s going to get better.”

Part of the problem is that pregnancy health care traditionally focused on the health and survival of the baby and not the long-term health of the mother, said Elliott Main, medical director of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative and professor at Stanford University School of Medicine.

CDC: All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika exposure

Medicaid, for example, kicks in automatically for pregnant women in most states, but runs out six weeks after they give birth, leaving low-income women at risk from lingering ailments, he said. The Texas task force report found that most of the state’s maternal deaths occurred after 42 days from birth.

California recently launched a statewide effort to expand care for expectant and recent mothers, such as increased hemorrhaging and hypertension tools and training, in hospitals across the state. Since the program’s launch, California’s maternal mortality has declined from 14 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2008 to around 10 per 100,000 births in 2014, Main said.

“You have to up your game,” he said. “Women today are more complicated. They’re heavier. They have more underlying conditions. If you don’t continually upgrade your care, you’re going to be behind the eight ball.”

That thinking is seeping slowly into Texas. State officials earlier this year introduced the Healthy Texas Women program, which provides extra services for pregnant women on Medicaid. And hospital chains have launched new initiative programs, such as “OB Navigators,” a system created by Harris Health System in which staffers guide mothers through prenatal, postpartum and primary care through pregnancy and beyond.

At the Center for Children and Women, open to those families who qualify for the Texas Children's Health Plan, staffers combine pediatrics, obstetrics, dental care, psychology and pharmacy under one roof to dispense a full network of care.

Meanwhile, the Texas task force, led by Hollier, will continue studying recent maternal deaths and expand on the findings of the report released earlier this year.

“Maternal mortality is an incredibly complex problems with a wide variety of contributing factors,” Hollier said. “This report is just the beginning.”